One of the ways novelists can be inventive is with…inventions.

Yes, some of their books weave stories around some of the greatest inventions in the history of humankind. That can certainly add drama and historic resonance to partly fact-based fiction.

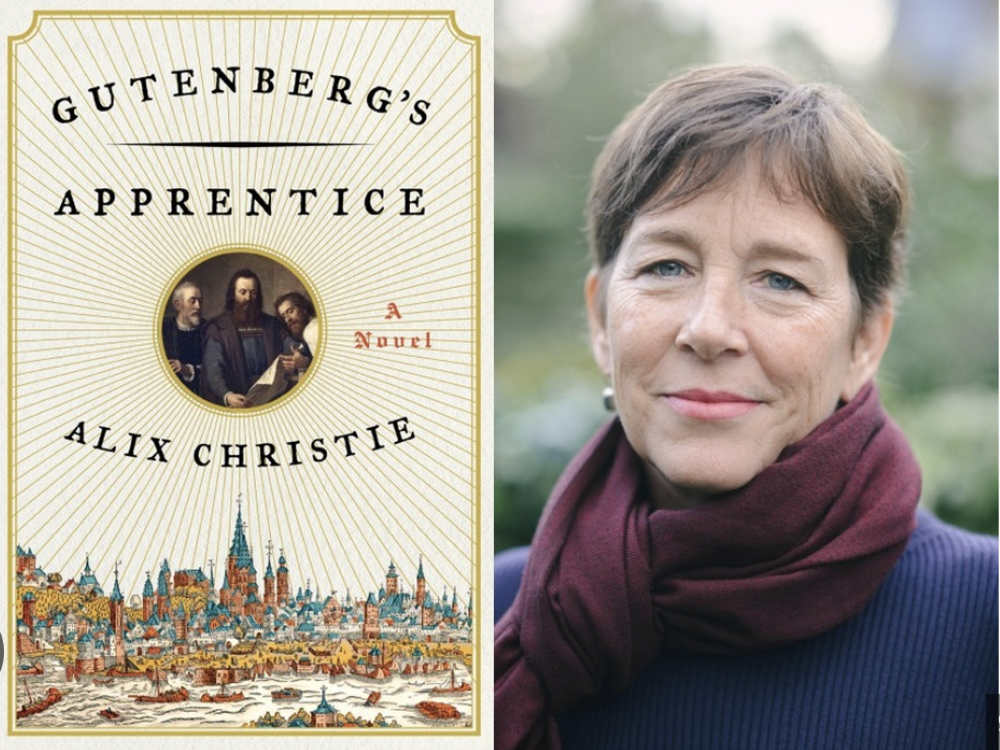

A prime example is Gutenberg’s Apprentice by Alix Christie, who tells the 15th-century story of a man who (at first reluctantly) helps the prickly, driven Johann Gutenberg develop the printing press — surely one of the most consequential inventions of all time. I’m currently in the middle of reading this absorbing 2014 novel.

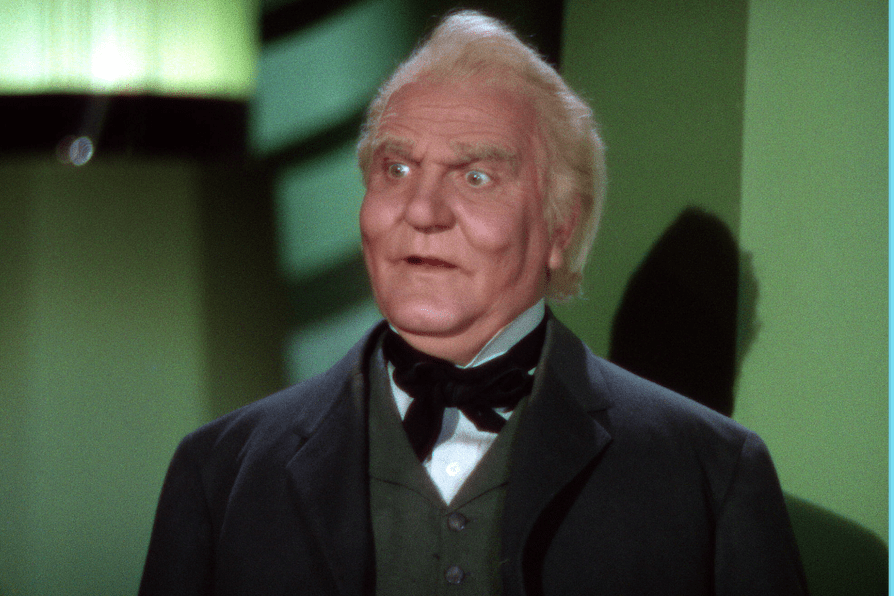

Part of The Magnificent Ambersons (1918) revolves around the invention and early days of the automobile — which figures in Booth Tarkington’s absorbing exploration of progress vs. stasis, and new money vs. old money.

Stephen King’s novel Cell takes a horror-laden (and satirical?) approach to cell phones as that technology was becoming widely popular. The book — perhaps my least-favorite King effort — features a mysterious broadcast over a cell-phone network that turns a bunch of people into zombie-like beings. 🙂 Published in 2006, a year before the iPhone was introduced.

The main focus of Mark Twain’s Pudd’nhead Wilson (1894) is the switching in infancy of two boys — one born into slavery and the other born to the master of the house. But a fascinating subplot features a court case in which the new technology of fingerprinting figures prominently. Interestingly, that new technology was anachronistically more current to when Twain wrote the novel than to the time period in which the novel was set.

Also anachronistic was Ayla’s much-too-early invention of the travois (a type of sled or platform, pulled by a horse, on which could be placed heavy loads) in Jean M. Auel’s circa-18,000 BC-set series that began with The Clan of the Cave Bear. The incredibly resourceful Ayla’s method of starting a fire was more contemporary to her prehistoric time.

Novels with time travel can certainly make inventions fascinating. For instance, the 20th-century physician Claire of Diana Gabaldon’s Outlander novels creates some homemade penicillin after she ends up living in the 18th century. Claire knew about that antibiotic because penicillin was discovered in 1928.

Another time travel book, Edward Bellamy’s Looking Backward (1888), was prescient in inventing an early version of a debit card — the modern version of which didn’t arrive until 1966.

Science fiction can of course also predict and depict inventions before they’re actually invented. One of countless examples is the spaceship from Earth in H.G. Wells’ 1901 novel The First Men in the Moon.

For younger readers, Danny Dunn and the Homework Machine by Raymond Abrashkin and Jay Williams took an early look at computers — which tended to be huge at the time of that novel’s 1958 publication.

Your thoughts on this topic? Other novels with a strong invention element?

My literary-trivia book is described and can be purchased here: Fascinating Facts About Famous Fiction Authors and the Greatest Novels of All Time.

In addition to this weekly blog, I write the 2003-started/award-winning “Montclairvoyant” topical-humor column every Thursday for Montclair Local. The latest piece — about a controversial project being voted on again, some overpaid municipal hires, and more — is here.