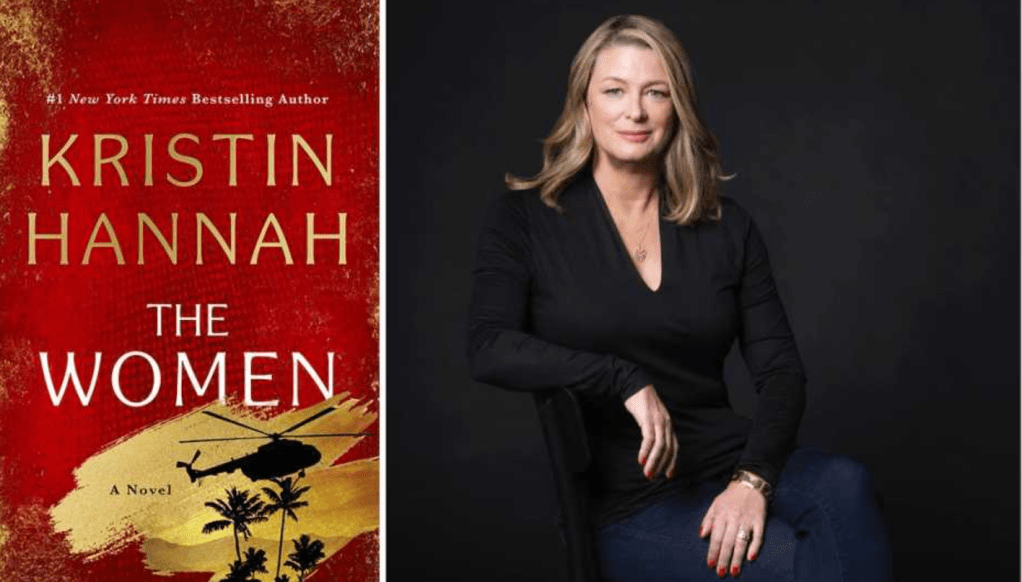

Kristin Hannah (St. Martin’s Press/Kevin Lynch)

Authors of course do research for not only nonfiction books but novels as well — often, albeit not always, when writing historical fiction. And sometimes the power of that research is…stunning.

I appreciated that once again last week when I read Kristin Hannah’s 2024 novel The Women, which focuses on U.S. combat nurses serving amid the chaos of the Vietnam War. The 1960-born Hannah was not a combat nurse, and hadn’t even reached adulthood before that war in Southeast Asia ended in 1975, but The Women‘s devastating “you are there” depiction of the work those nurses did is unforgettable. She obviously researched things to the hilt — reading written sources as well as interviewing people — and then combined that with a riveting story, compelling characters, and excellent prose and dialogue.

This was not the first time Hannah tackled historical fiction; among her many previous books are well-researched novels starring women such as The Nightingale (set during World War II) and The Four Winds (which unfolds in the 1930s Depression/Dust Bowl/California milieu previously explored by John Steinbeck in his classic The Grapes of Wrath).

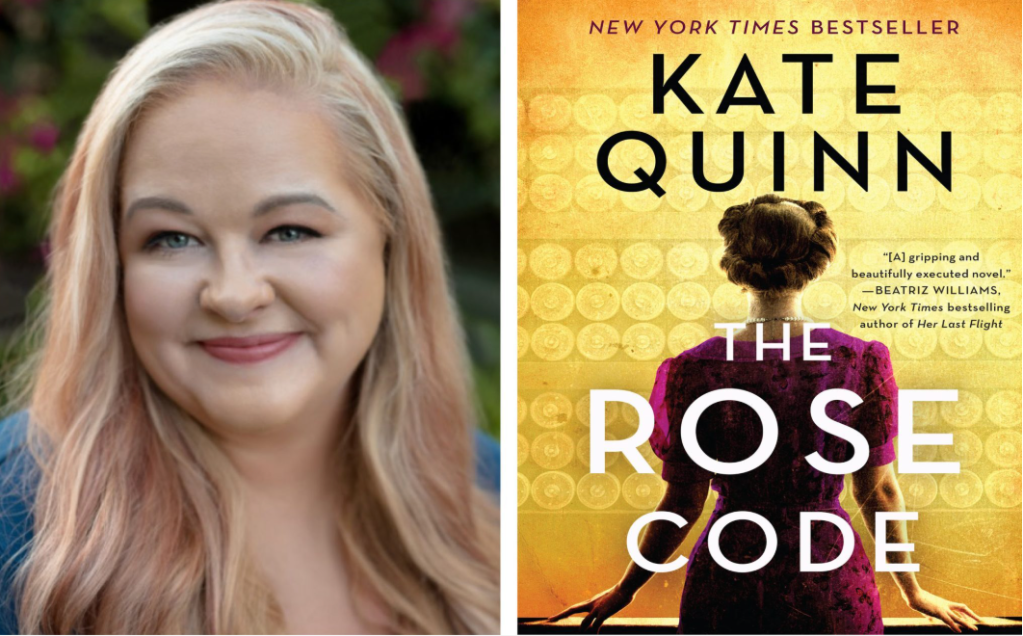

With the help of careful/thorough research, female authors can obviously write novels set during wartime or other fraught times that are as good or better than those by male authors. We see that in such titles as Isabel Allende’s The House of the Spirits (which includes content about the U.S.-backed 1973 military coup in Chile); Julia Alvarez’s In the Time of the Butterflies (battling a Dominican Republic dictatorship); Kate Quinn’s The Rose Code and The Huntress as well as Elsa Morante’s History (all World War II-related); Quinn’s The Alice Network, Pat Barker’s Regeneration, Willa Cather’s One of Ours, and L.M. Montgomery’s Rilla of Ingleside (all World War I-related); Toni Morrison’s Beloved, Margaret Mitchell’s Gone With the Wind, and Geraldine Brooks’ March (all American Civil War-related); Octavia E. Butler’s Kindred and Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin (brutal U.S. slavery times); Diana Gabaldon’s Outlander series (American Revolutionary War); and Hilary Mantel’s Wolf Hall (intrigue in early 16th-century England).

Other historical novels that grab reader interest with the help of research-buttressed story lines and characters include Barbara Kingsolver’s The Lacuna, Margaret Atwood’s Alias Grace, Alix Christie’s Gutenberg’s Apprentice, Amor Towles’ A Gentleman in Moscow, Khaled Hosseini’s The Kite Runner, Mark Twain’s Personal Recollections of Joan of Arc, Nathaniel Hawthorne’s The Scarlet Letter, Alex Haley’s Roots, Junot Diaz’s The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao, Tracy Chevalier’s Girl With a Pearl Earring and Remarkable Creatures, E.L. Doctorow’s Ragtime and The Book of Daniel, and Sir Walter Scott’s Ivanhoe and Rob Roy, to name just a few.

Also, I will be reading Colson Whitehead’s The Underground Railroad sometime next month.

There are obviously countless well-researched novels out there; what are some of the ones you’d like to discuss, whether they were mentioned in my post or not? Any general comments about author research?

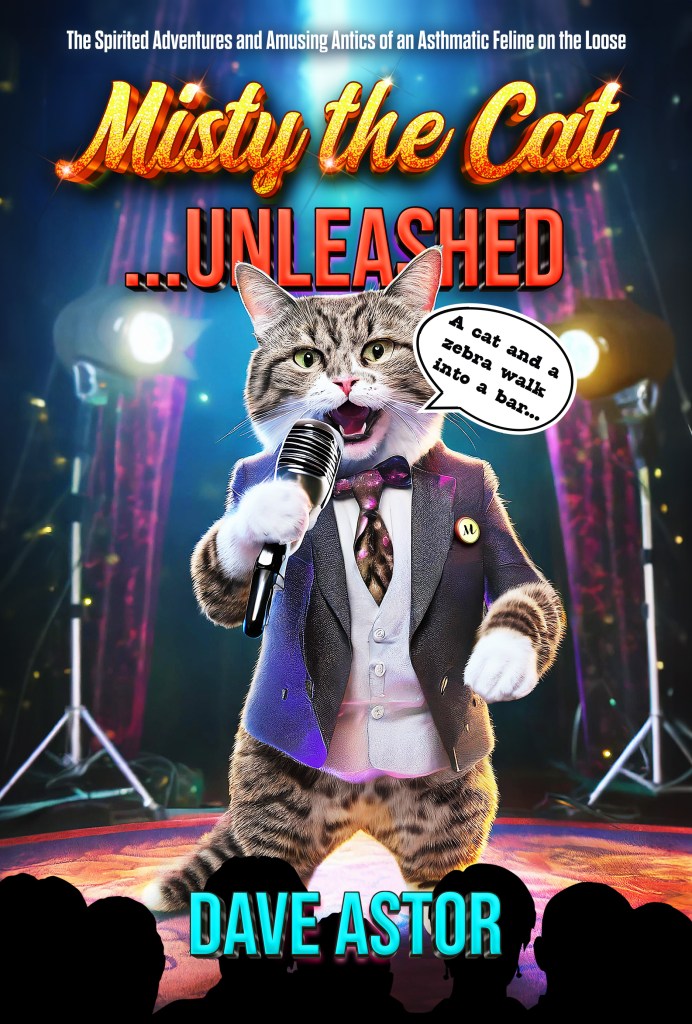

Misty the cat says: “Those are either daffodils in the distance or unusual cell towers.”

My comedic 2024 book — the part-factual/part-fictional/not-a-children’s-work Misty the Cat…Unleashed — is described and can be purchased on Amazon in paperback or on Kindle. It’s feline-narrated! (And Misty says Amazon reviews are welcome. 🙂 )

This 90-second promo video for my book features a talking cat: 🙂

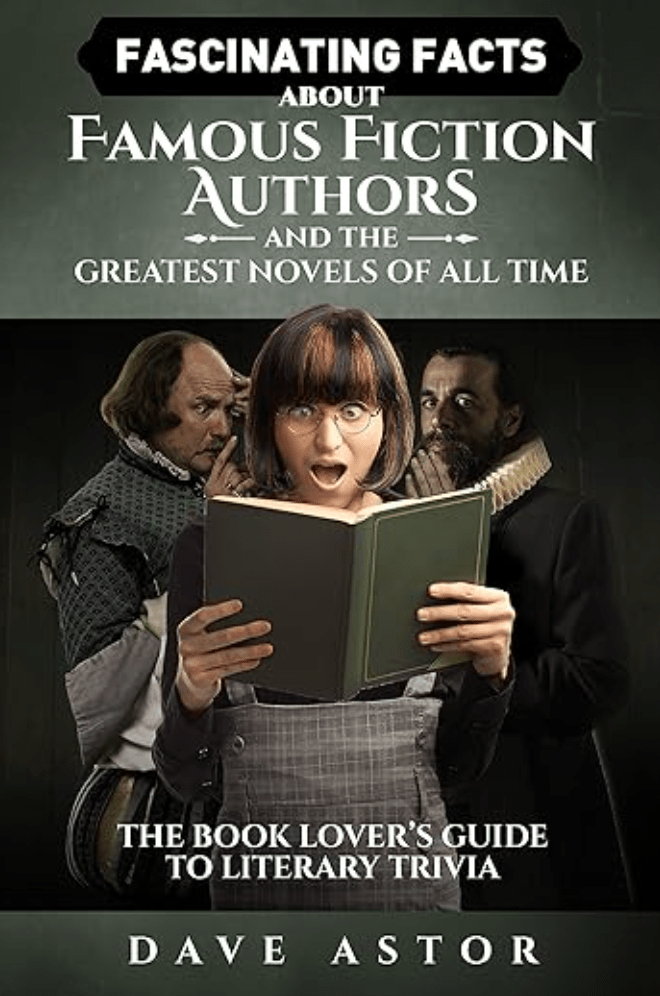

I’m also the author of a 2017 literary-trivia book…

…and a 2012 memoir that focuses on cartooning and more.

In addition to this weekly blog, I write the 2003-started/award-winning “Montclairvoyant” topical-humor column every Thursday for Montclair Local. The latest piece — about a new library bond, an old school district bond, a faltering gubernatorial candidate, mice in a school, a welcome transgender proclamation, and more — is here.