Tommy Orange and his novel.

Amid the big pleasures of reading fiction are some small pleasures, and one of them is when a novel’s title appears in the body of the book.

I’m of course not talking about novels whose titles are a person or place; those names will inevitably be mentioned multiple times in a book’s pages. I’m talking about the more evocative matter of novels with titles you might initially puzzle over, or with titles you’re kind of familiar with but are curious how they’ll be used in the book.

I just read There There, whose title can be interpreted in various ways. Tommy Orange’s impressive, compelling, VERY painful 2018 novel focuses on about a dozen contemporary Native-American characters — mostly residents of Oakland, Calif., and its urban milieu. Many of the characters are struggling with racism (at the hands of the white power structure), poverty, broken families, addiction, and other problems. They are “accidents waiting to happen,” which happens to be a line in Radiohead’s 2003 song “There There” — a song Orange mentions in the book. Later on, the author also mentions Gertrude Stein’s famous quote “There is no there there” — about…Oakland, Calif.

On top of that, Orange constantly bounces the narrative from one character to another, or, to put it a different way, from one household (there) to another household (there). Finally, we think of “there, there…” as a phrase expressing sympathy — something many of Orange’s characters can use, especially during the novel’s shattering climax.

Another impressive, compelling, VERY painful recent novel — Angie Thomas’ The Hate U Give — has a title many readers have heard somewhere before. Sure enough, the book mentions rapper Tupac Shakur’s concept of “THUG LIFE”: “The Hate U Give Little Infants Fucks Everybody.” The traumatic events in Thomas’ 2017 novel — about a white cop’s murder of a young black man and what ensues — certainly bear that out.

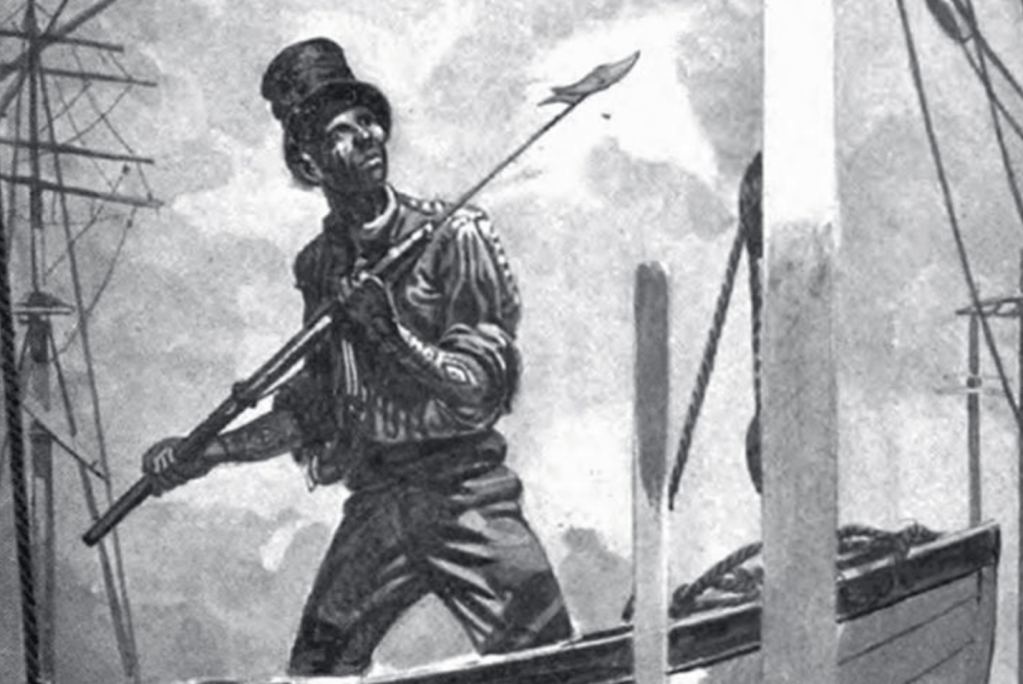

The two words in Zadie Smith’s intriguingly titled White Teeth show up more than once in her multiethnic novel. Those words refer to how people of all types are essentially the same (most originally have white teeth) yet have some differences (teeth can turn yellow or be in various other conditions). And one way racism is historically mentioned in Smith’s novel is via the horrid memory of racist/murderous white soldiers spotting vulnerable Africans in the dark by the contrast of their white teeth and dark skin.

John Steinbeck’s The Grapes of Wrath has a title that of course conveys the anger of exploited, impoverished people (including the Joad family) treated badly by such entities as American big business and law enforcement. But will those four words, also known for being part of the 19th-century “Battle Hymn of the Republic,” turn up in the novel? They do, in this memorably striking passage: “…and in the eyes of the people there is the failure; and in the eyes of the hungry there is a growing wrath. In the souls of the people the grapes of wrath are filling and growing heavy, growing heavy for the vintage.”

In some cases, readers think a title means one thing but it turns out to mean something else when the words pop up in the novel — an ambiguity often crafted deliberately by the authors. For instance, the latest Jack Reacher thriller by Lee Child and Andrew Child is called The Sentinel and one of course thinks of someone who stands guard. But we eventually learn that “The Sentinel” is the name of a software program pivotal to the novel’s plot.

Any examples you’d like to offer that fit the theme of this post?

My literary-trivia book is described and can be purchased here: Fascinating Facts About Famous Fiction Authors and the Greatest Novels of All Time.

In addition to this weekly blog, I write the 2003-started/award-winning “Montclairvoyant” topical-humor column for Baristanet.com. The latest weekly piece — which looks at allegations of mayoral conflicts of interest — is here.