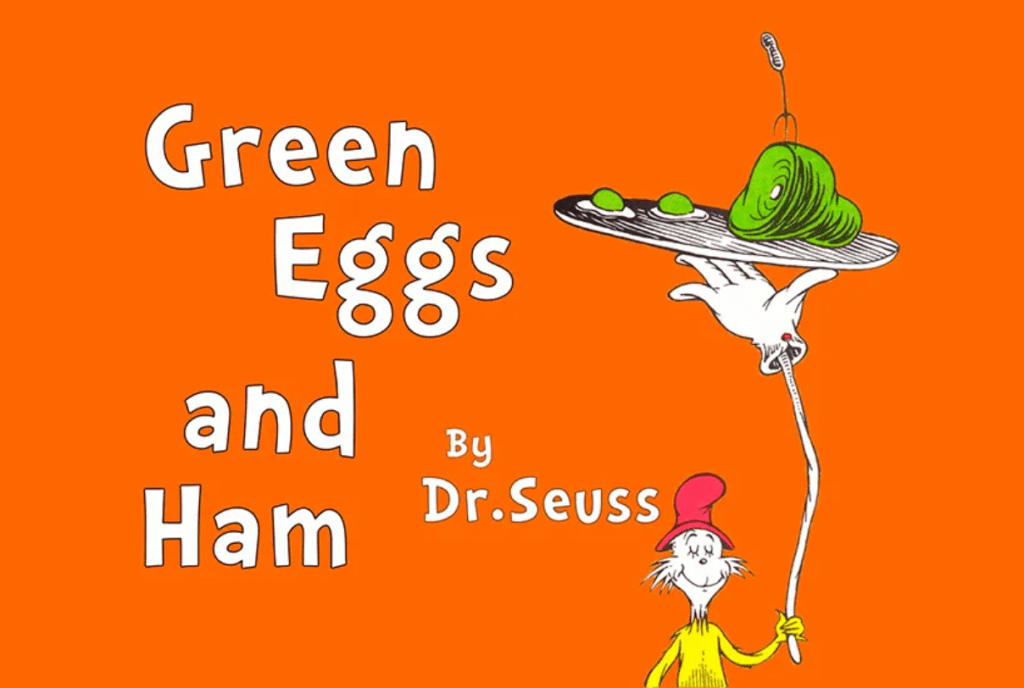

Credit: Random House

Authors dealing with restrictions can find their literary creativity stifled or stimulated. This post will discuss several examples of the latter.

Some fiction fans know the story behind the iconic Green Eggs and Ham. Dr. Seuss was challenged to do a children’s book containing a maximum of 50 different words (albeit all of which could be used more than once). The author struggled with that parameter, but eventually created what has been an enduring bestseller since 1960.

Moving to adult novels, Margaret Atwood was asked to write a book retelling a classic myth of her choosing — so the Canadian author obviously had a limitation on subject matter. She decided to do a feminist take on Homer’s Odyssey, focusing on Odysseus’ wife Penelope and other women. The result was 2005’s The Penelopiad. Not one of Atwood’s most compelling novels, but worth reading.

Another way of working within a framework is writing a novel in verse. Such was the case with Eugene Onegin (1833) by Russian author Alexander Pushkin, whose titular protagonist is a young, selfish, arrogant dandy. While one wouldn’t expect an all-poetry work to be as gripping as a more traditional prose novel, Eugene Onegin holds one’s interest and then some.

Russian-turned-American author Vladimir Nabokov also gave himself a challenge with Pale Fire (1962), which contains a lengthy poem along with prose. A brilliant novel, but not exactly a warm novel — despite having fire in its title. 🙂

Then there are novels written in countries ruled by dictatorial regimes, meaning that if the authors want to satirize said regimes they need to be indirect and allegorical to try avoid possible prison or death. One example is The Master and Margarita, a rollicking novel that Mikhail Bulgakov wrote between 1928 and 1940 in the Stalin-led Soviet Union.

There are also the creative restrictions involved with co-authoring a novel, because it’s not “the baby” of just the usual solo writer. Among such books is 1873’s The Gilded Age by Charles Dudley Warner and Mark Twain. Each man mostly wrote separate chapters, though they reportedly jointly penned a few. The result was an awkward fit; one could tell that the satirical chapters were Twain’s, although Warner’s serious/more-conventional sections weren’t bad.

Finally, I recently read Past Lying (2023), the seventh installment of Scottish author Val McDermid’s series starring cold-case detective Karen Pirie. McDermid imposed restrictions of a sort on herself by setting the novel during 2020’s Covid lockdown, which gave Pirie and her police colleagues quite a logistical challenge investigating a twisty case of murder committed by a crime author. But McDermid pulled it off; I think Past Lying is the best of the Pirie series.

Any comments about, and/or examples of, this topic?

Many thanks to “The Introverted Bookworm” — talented blogger/author Ada Jenkins — for the wonderful review of my 2017 literary-trivia book she posted this past Tuesday, May 27. Very, very appreciated! 🙂

Misty the cat says: “Every cat needs a vacation home.”

My comedic 2024 book — the part-factual/part-fictional/not-a-children’s-work Misty the Cat…Unleashed — is described and can be purchased on Amazon in paperback or on Kindle. It’s feline-narrated! (And Misty says Amazon reviews are welcome. 🙂 )

This 90-second promo video for my book features a talking cat: 🙂

I’m also the author of the aforementioned 2017 literary-trivia book…

…and a 2012 memoir that focuses on cartooning and more.

In addition to this weekly blog, I write the 2003-started/award-winning “Montclairvoyant” topical-humor column every Thursday for Montclair Local. The latest piece — about Memorial Day, a local food pantry, and more — is here.