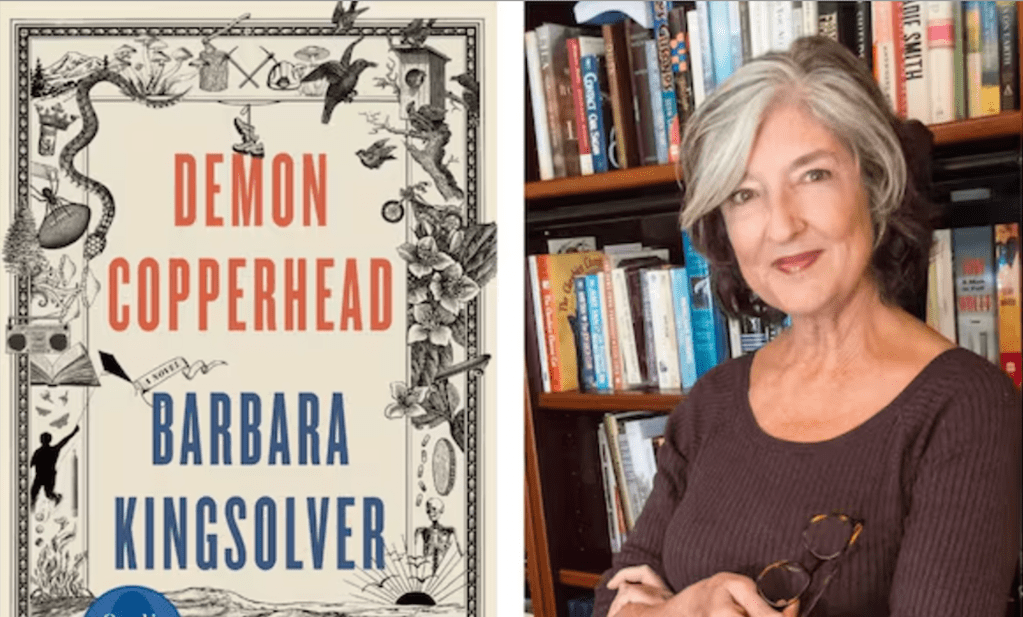

(Courtesy of Harper.)

Elvis Presley sang “Return to Sender.” Today, I’m going to…return to gender. Heck, I’m not even a Presley fan, so excuse my blog-post opening as I write about characters who are the opposite sex of their novelist creators.

While female authors have created many of the most-memorable female protagonists and male authors have created many of the most-memorable male protagonists, skillful novelists can of course successfully cross gender lines. It takes some imagination, some research, and some drawing on experiences with opposite-sex parents, spouses, siblings, children, friends, work colleagues, etc. And authors can obviously include memorable co-stars and supporting characters of the same gender as themselves.

For the purposes of this blog post, I’m going to focus on characters who are in the novels’ titles.

An example of today’s theme that I finally read last week is Barbara Kingsolver’s tour de force Demon Copperhead, the 2022 coming-of-age story of a boy who faces poverty, the death of his parents, foster care, addiction, injury, and other enormous challenges. It’s uncanny how well a female author in her late 60s gets into the psyche of a male who’s a preteen or teen during virtually the entire Pulitzer Prize-winning book — for which Kingsolver took inspiration from Charles Dickens’ 1850 classic David Copperfield while transferring the time and setting from 19th-century England to late-20th-century/early-21st-century Appalachia in the United States.

After finishing Demon Copperhead, I read Gabrielle Zevin’s The Storied Life of A.J. Fikry (2014) — about the prickly (male) owner of an island bookstore. A funny and poignant short novel with some echoes of George Eliot’s compelling classic Silas Marner.

About 150 years earlier, Eliot was an accomplished female author with a male title character in three of her five best-known novels: Adam Bede (1859), Daniel Deronda (1876), and the aforementioned Silas Marner (1861). All three of those men are quite believable and three-dimensional, even as prominent female characters steal (or almost steal) the show.

The 19th century also saw the publication of such female-written works as Mary Shelley’s mega-influential Frankenstein (1818), George Sand’s Jacques (1833), Elizabeth Gaskell’s Mr. Harrison’s Confessions (1851), and Harriet Beecher Stowe’s cry-for-justice Uncle Tom’s Cabin (1852), among other novels.

Moving into the 20th century and beyond, we have Edith Wharton’s emotionally wrenching Ethan Frome (1911), Willa Cather’s okay debut novel Alexander’s Bridge (1912), Colette’s Cheri (1920) and The Last of Cheri (1926), Agatha Christie’s The Murder of Roger Ackroyd (1926), Lord Edgware Dies (1933), and Hercule Poirot’s Christmas (1938), Alice Walker’s The Third Life of Grange Copeland (1970), and (you knew I would get to this eventually 🙂 ) J.K. Rowling’s blockbuster Harry Potter series of seven books published between 1997 and 2007.

And we can’t forget Murasaki Shikibu’s VERY early female-authored-novel-starring-a-man The Tale of Genji, written in the early 11th century.

Given that there were many more male than female authors published pre-1900, we can easily find a slew of male-written novels back then with female title characters: Daniel Defoe’s Moll Flanders (1722), Samuel Richardson’s Pamela (1740), Honore de Balzac’s Eugenie Grandet (1833), Gustave Flaubert’s Madame Bovary (1856), Charles Dickens’ Little Dorrit (1857), Lewis Carroll’s Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland (1865), Emile Zola’s Therese Raquin (1867) and Nana (1880), R.D. Blackmore’s Lorna Doone (1869), Thomas Hardy’s The Hand of Ethelberta (1876) and Tess of the d’Urbervilles (1891), Leo Tolstoy’s Anna Karenina (1878), Henry James’ Daisy Miller (1878), and Mark Twain’s Personal Recollections of Joan of Arc (1896), to name a few.

Plenty of titles after that, too, such as Theodore Dreiser’s Sister Carrie (1900), Herman Wouk’s Marjorie Morningstar (1955), William Styron’s Sophie’s Choice (1979), Walter Mosley’s Rose Gold (2014), and multiple ones by Stephen King — including Carrie (1974), Dolores Claiborne (1992), and Rose Madder (1995).

Your thoughts about, and examples of, this theme?

Misty the cat says: “I’m Nancy Drew starring in ‘The Mystery of the Aromatic Leaves.'”

My comedic 2024 book — the part-factual/part-fictional/not-a-children’s-work Misty the Cat…Unleashed — is described and can be purchased on Amazon in paperback or on Kindle. It’s feline-narrated! (And Misty says Amazon reviews are welcome. :-) )

This 90-second promo video for my book features a talking cat: 🙂

In addition to this weekly blog, I write the 2003-started/award-winning “Montclairvoyant” topical-humor column every Thursday for Montclair Local. The latest piece — about my town’s harassed CFO, unaffordable housing, an environmentally awful plan to cut down many trees, and more — is here.