The wedding in A Walk to Remember‘s movie version. (Screen shot by me.)

I’ll be attending a family wedding this coming weekend, so naturally I’ll write today about…weddings in literature.

As in real life, fictional weddings can be wonderful and/or weird and/or lavish and/or bare bones and/or dramatic and/or problematic and/or heartwarming and/or…whatever.

One of the most famous fictional wedding ceremonies is that of the title character and Edward Rochester in Charlotte Bronte’s 1847 classic Jane Eyre. They are a couple very much in love, but, as many of you know, Rochester has quite a secret. Will it be revealed before the duo says “I do”?

Also memorable is the union of Gervaise and Coupeau in Emile Zola’s 1877 novel The Drinking Den. The couple spend more money on the nuptials than they can afford, the priest who marries them is surly, and the guests get lost in The Louvre museum while killing time between the ceremony and reception. Gervaise had been reluctant to marry Coupeau, or any man, and the imperfect wedding is a harbinger of the disasters that will follow after a few years of happiness.

Their daughter would meet with her own disasters in a subsequent Zola novel, 1880’s Nana.

In Diana Gabaldon’s Outlander, the wedding of Claire and Jamie takes place not long after Claire involuntarily time-travels from the 1900s to the 1700s. The two barely know each other, and the union is basically forced — making for a tension-filled yet partly humorous situation. But, lo and behold, the 20th-century-born Claire and the 18th-century-born Jamie by chance end up being very compatible even as they face many daunting challenges in the rest of the novel and its sequels.

Claire and Jamie tied the knot in the first Outlander book, but sometimes it pays to build things up more gradually. For instance, Anne Shirley and Gilbert Blythe have like-dislike interactions in L.M. Montgomery’s Anne of Green Gables and beyond. It’s not until the fourth sequel — Anne’s House of Dreams — that they marry. The wedding scene, and Montgomery’s writing of it, are worth the wait. As with Claire and Jamie, Anne and Gilbert are ultimately compatible.

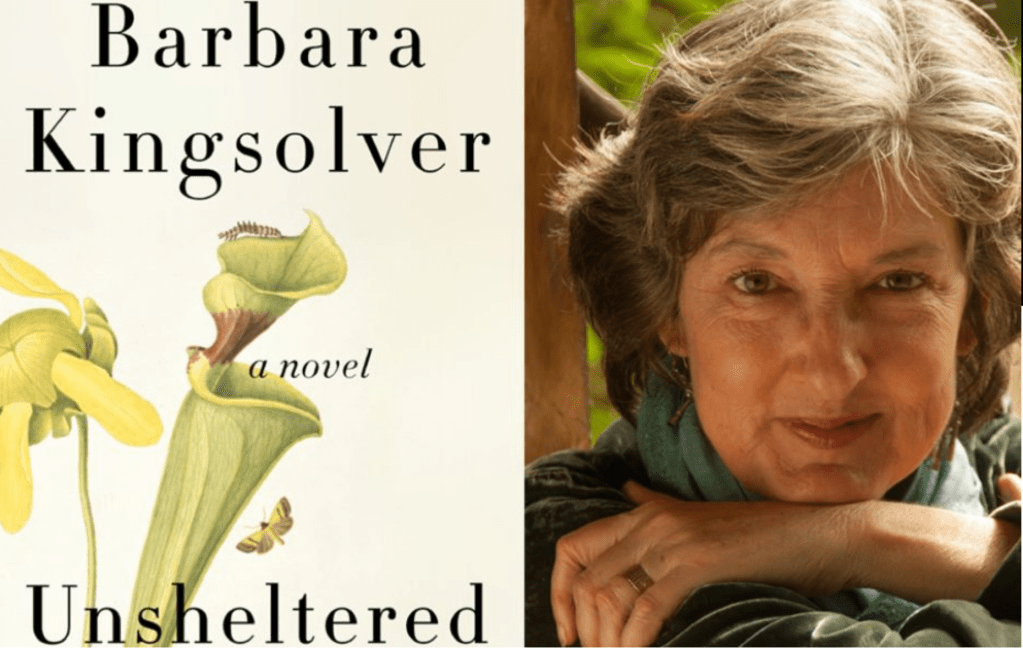

Nicholas Sparks’ tear-jerker A Walk to Remember features the unexpected high-school-student relationship between the popular Landon and the ostracized Jamie, who’s immensely good-hearted but considered “uncool” for dressing poorly and being religious. We learn she is terminally ill, but the two teens marry anyway in a beautiful ceremony. The novel, whose story is told 40 years later by Landon, leaves things ambiguous as to whether Jamie died or not.

Then there’s the wedding element in Charles Dickens’ 1861 novel Great Expectations. Miss Havisham was jilted at the altar by a scoundrel, and becomes a bitter/depressed recluse who never gets over the traumatic nuptials experience she had as a young woman.

On a more upbeat note, Jane Austen novels are known for a number of “happy ending” weddings after complications and obstacles are overcome. The marriage ceremonies tend to be mentioned more than actually depicted.

Your thoughts about, and examples of, today’s theme?

My next blog post will run on Monday, May 8, rather than the usual Sunday.

My literary-trivia book is described and can be purchased here: Fascinating Facts About Famous Fiction Authors and the Greatest Novels of All Time.

In addition to this weekly blog, I write the 2003-started/award-winning “Montclairvoyant” topical-humor column for Baristanet.com every Thursday. The latest piece — about two Black firefighters suing over blatant racism in my town’s “leadership” — is here.