St. John in the Virgin Islands. (Credit: Visit USVI.)

A number of authors set their novels in the same place. So, it becomes quite noticeable when they set their novels in…a different place.

This surprise can be welcome or not, depending on the reader and how good the books are. But a change-of-pace is often a good thing, for both the writers and their fans wanting to avoid a “rut.” The authors might have to do a little more research, but they’ll survive. 🙂

I most recently enjoyed a setting switch in the work of Elin Hilderbrand. She is known for placing her novels on Nantucket, and I have loved the ones I’ve read featuring that Massachusetts island milieu. Then I picked up Hilderbrand’s Winter in Paradise, thinking I was returning to Nantucket — only to find that the novel was mostly set on St. John in the Virgin Islands. That was initially a bit disorienting, but Winter in Paradise turned out to be another compulsively readable Hilderbrand book…this time about how a family’s life changes when they learn the father had a secret second family. Then I quickly finished the second and third installments of the trilogy: What Happens in Paradise and Troubles in Paradise — the latter book ending with a dramatic and destructive hurricane. I’m sure it helped the Nantucket-based Hilderbrand in writing the trilogy that she visits St. John for several weeks each year as a warm-weather writing retreat and vacation spot.

Among the other authors who’ve produced the occasional geographic surprise is Sir Walter Scott, who placed most of his historical novels in Scotland but situated Quentin Durward in France. Still, the archer Quentin is Scottish, so Sir Walter didn’t stray completely from his own real-life roots.

Charles Dickens usually used London as the locale for his novels, but did set part of A Tale of Two Cities in Paris and part of Martin Chuzzlewit in the United States.

Given that travel was much more difficult and time-consuming during the pre-1900 era in which writers such as Scott and Dickens lived, it’s not surprising that many long-ago authors kept their novels pretty close to the locales they knew most in a firsthand way. But Dickens did take two extended trips to the U.S., and Scott visited France (though after Quentin Durward was published). Also, Scott’s wife Charlotte was of French descent.

Another 19th-century author, Mark Twain, was among the most globetrotting Americans of his time — which bore fruit in such novels as A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur’s Court (England) and Personal Recollections of Joan of Arc (France), and in his hilarious nonfiction travel masterpiece The Innocents Abroad (in which Twain chronicled his visits to many places, including the Mideast).

In post-1900 literature, William Faulkner virtually always set his novels in Mississippi, but three of his books unfolded elsewhere: including France in A Fable.

Barbara Kingsolver also placed the vast majority of her novels in the U.S. (usually Appalachia, the South, or the Southwest), but sent her American characters to Africa in The Poisonwood Bible and situated a large portion of The Lacuna in Mexico.

Your thoughts about, and example of, this theme?

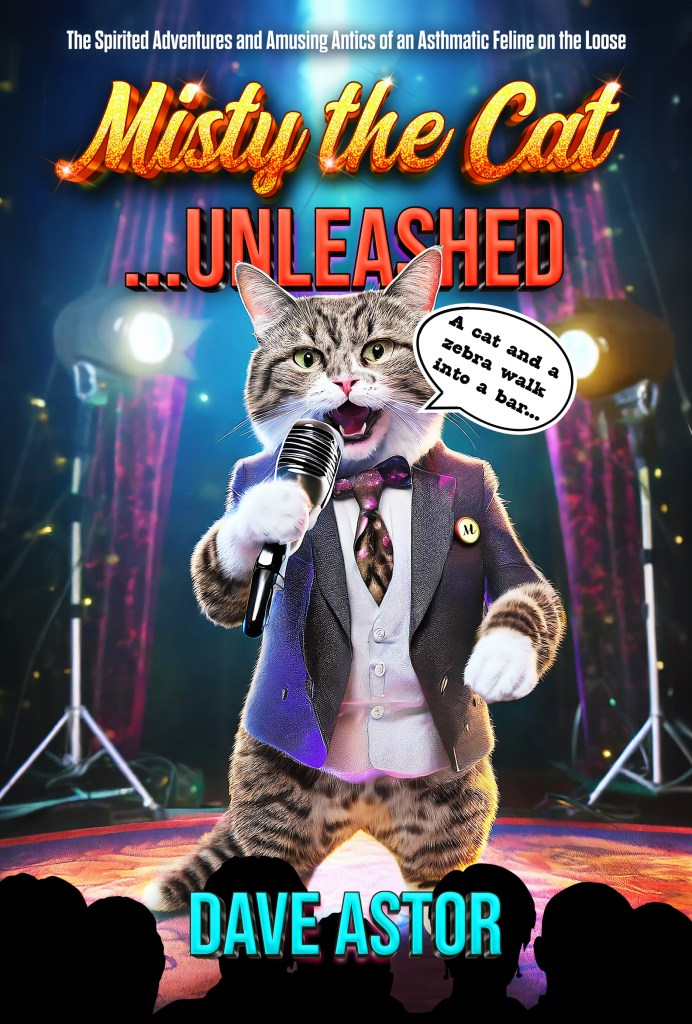

Misty the cat says: “Orange skies don’t appear like clockwork; what was Anthony Burgess thinking?”

My comedic 2024 book — the part-factual/part-fictional/not-a-children’s-work Misty the Cat…Unleashed — is described and can be purchased on Amazon in paperback or on Kindle. It’s feline-narrated! (And Misty says Amazon reviews are welcome. 🙂 )

This 90-second promo video for my book features a talking cat: 🙂

In addition to this weekly blog, I write the 2003-started/award-winning “Montclairvoyant” topical-humor column every Thursday for Montclair Local. The latest piece — about a possible end to free holiday parking and a local U.S. congresswoman’s entry into New Jersey’s governor race — is here.