Yesterday, a massive total of nearly seven million people attended the 2,700-plus “No Kings” rallies in the United States and abroad to protest Trump’s fascist/authoritarian regime as that Republican administration ignores Congress, enriches itself, cracks down on peaceful dissent, arrests innocent people of color, invades American cities for no good reason, meddles in other countries’ affairs, starts or supports wrongful military actions around the world, etc. Which, as a literature blogger, reminded me of kings and other royalty in fiction — including historical fiction.

Of course, some royalty can be partly benevolent, but in many cases all that power heightens a ruler’s nasty instincts, makes a corrupt person even more corrupt, and increases the entitlement of the already entitled. Also, being a member of royalty doesn’t exactly involve the merit system.

I’ve never deliberately sought out novels containing royal characters, much preferring to read about the lives of “everyday” people. But privileged aristocrats have popped up here and there in my reading.

For instance, when long ago working through many a great book by Mark Twain, I polished off The Prince and the Pauper (two boys changing places) and A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur’s Court (in which a certain king appears).

Another 19th-century novel, Alexandre Dumas’ 17th-century-set The Three Musketeers, includes King Louis XIII and Queen Anne as secondary characters.

In Charles Dickens’ A Tale of Two Cities, King Louis XVI and King George III are referenced.

Some novels written in the 20th and 21st centuries also include royal characters. Hilary Mantel’s Wolf Hall has Henry VIII and other monarchical personages, Josephine Tey’s The Daughter of Time harkens back to King Richard III, Robert Graves’ I, Claudius features the Roman emperor of the book’s title, J.R.R. Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings has the would-be king Aragorn, and Philippa Gregory’s Earthly Joys has the Duke of Buckingham.

There’s also William Goldman’s The Princess Bride, Meg Cabot’s The Princess Diaries, Antoine de Saint-Exupery’s The Little Prince, Lewis Carroll’s Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland and its Queen of Hearts, C.S. Lewis’ The Chronicles of Narnia and its King Tirian, Diana Gabaldon’s Outlander and its King Louis XV appearance, Margaret Landon’s Anna and the King of Siam that inspired The King and I musical, and so on.

Of course there’s royalty, too, in various Shakespeare plays and in other stage creations such as Eugene O’Neill’s The Emperor Jones, Lin-Manuel Miranda’s Hamilton (King George III), etc.

I’m sure I’ve only touched the surface here. Any additional examples of, or thoughts about, this topic?

Misty the cat asks: “What’s the new White House ballroom doing here?”

My comedic 2024 book — the part-factual/part-fictional/not-a-children’s-work Misty the Cat…Unleashed — is described and can be purchased on Amazon in paperback or on Kindle. It’s feline-narrated! (And Amazon reviews are welcome. 🙂 )

This 90-second promo video for the book features a talking cat: 🙂

I’m also the author of a 2017 literary-trivia book…

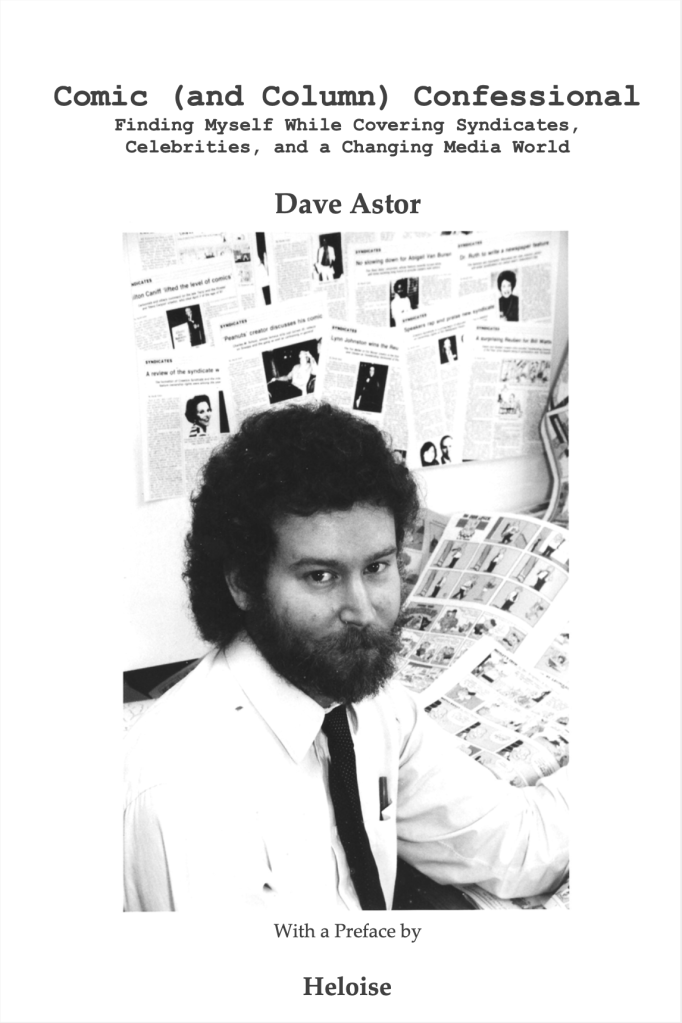

…and a 2012 memoir that focuses on cartooning and more, and includes many encounters with celebrities.

In addition to this weekly blog, I write the 2003-started/award-winning “Montclairvoyant” topical-humor column every Thursday for Montclair Local. The latest piece — about wondering how to vote in a controversial local tax referendum that will be held this December because of a huge school district deficit — is here.