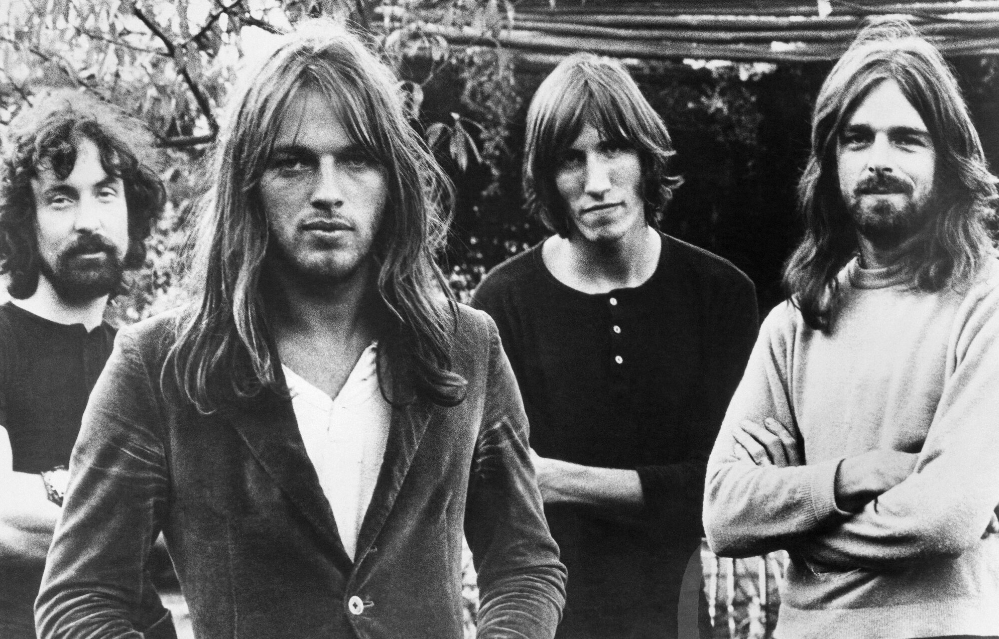

My town’s Montclair Book Center, August 19, 2023. (Photo by me.)

Last week, I discussed some libraries in my life. This week, I’m following that up by focusing on some bookstores in said life.

I’ll start with my New Jersey town of Montclair, which has two independent bookstores — unusual for a suburb of about 40,000 people.

One of those retailers is Montclair Book Center, which opened in 1984 (thanks, George Orwell 🙂 ) but appealingly feels much older. Rather scruffy-looking, but filled with a ton of new and used titles in its crowded aisles. I can’t count the number of book (and calendar) gifts I’ve purchased there over the years.

The second Montclair literary haven is the less quirky but quite nice Watchung Booksellers, a mere five-minute walk from my apartment.

In nearby New York City, where I lived and worked for many years, perhaps the most memorable bookstore is the renowned Strand — which has 2.5 million new, used, rare, and out-of-print books. Formerly also very convenient, given that the Manhattan-based magazine for which I used to write was only two blocks down Broadway in the East Village.

Among my memories of shopping at the Strand, from when I was in my mid-20s, was surprising a woman I was dating at the time with a present of a very hard-to-find book she said she’d been seeking for years. The Strand had it in stock during those pre-Amazon days. But the woman was rather blasé about the gift, and we didn’t date much longer. 🙂

Further afield in the United States, I have fond memories of visiting famous bookstores such as City Lights in San Francisco and Powell’s in Portland, Oregon. And a not-so-famous one in Tennessee whose name I can’t remember — but I recall several other things about that 1991 experience.

I was in Memphis to cover the Association of American Editorial Cartoonists convention for a magazine when a free afternoon allowed me to walk around the city with Jerry Robinson, whose many accomplishments in cartooning included creating the iconic character of The Joker (and naming sidekick Robin) while working on the Batman comic books as a pre-World War II teen. Anyway, we found a great shop with comic books and other cartoon items — and Jerry, who was 69 at the time, was like a kid in a candy store. Needless to say, he made several purchases.

While I prefer independent bookstores to chain ones (especially indies with cats 🙂 ), I’ve certainly frequented some nice Barnes & Noble outlets. The now-defunct Borders, too; I even visited its flagship store in Ann Arbor with my wife Laurel — who spent the majority of her childhood in that Michigan city.

Airport bookstores? Usually pretty basic, but they’ve come in handy at times.

After flying to Paris, one has to at least browse the many outdoor book kiosks near the Seine — as I’ve done several times. And I found a bookstore in Moscow many years ago that featured some English-language offerings among its Russian-language titles. I still have Nikolai Ostrovsky’s novel How the Steel Was Tempered from that visit.

Bookstores you have known?

My literary-trivia book is described and can be purchased here: Fascinating Facts About Famous Fiction Authors and the Greatest Novels of All Time.

In addition to this weekly blog, I write the 2003-started/award-winning “Montclairvoyant” topical-humor column for Baristanet.com every Thursday. The latest piece — about an “emergency” meeting that wasn’t an emergency, and more — is here.