Every decade has its share of memorable novels. Today I’m going to focus on the 1880s.

Every decade has its share of memorable novels. Today I’m going to focus on the 1880s.

Why? Because I recently finished a spellbinding 1887 book called She. An imperfect novel — author H. Rider Haggard has some troubling views on race, gender, and class even as he can be relatively enlightened for his time — but also a book that offers an eerie take on mortality and immortality (the ruthless but at times sympathetic title character, shown above, is 2,200 years old!). A thrilling adventure tale that contains many philosophical ruminations and impressive writing flourishes.

The 1880s were semi-dominated by multiple great novels from Henry James, Mark Twain, and Emile Zola, but that long-ago decade essentially began in a literary sense with the 1880 classic The Brothers Karamazov. Fyodor Dostoyevsky’s book is more sprawling and uneven than his 1866 masterpiece Crime and Punishment, but when Brothers is good it’s amazing. Dostoyevsky reportedly intended the novel to be the first of a trilogy, but he died in early 1881.

Another 19th-century Russian writing legend, Leo Tolstoy, sort of ended the decade’s literary output with one of his best short novels — 1889’s gripping and controversial The Kreutzer Sonata.

But back to the three authors who semi-dominated the decade. Henry James started things off with the compelling Washington Square (1880), about a not-nice doctor and his sweet-but-dull daughter; and then wrote what is my favorite novel of his, the heartbreaking classic The Portrait of a Lady (1881). Among James’ many other works during those productive years was The Aspern Papers (1888), about an obsessed man trying to get his hands on the letters and such of a famous dead poet by ingratiating himself with that poet’s aged lover.

Mark Twain? There was The Prince and the Pauper (1881), Adventures of Huckleberry Finn (1884), and A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur’s Court (1889). Huckleberry Finn, of course, is considered Twain’s best novel — and it totally deserves that designation despite faltering a bit in the last third when Tom Sawyer makes an annoying and unwelcome appearance. Connecticut Yankee, an early time-travel work, is fiercely antiwar amid the frequent hilarity.

Zola zoomed through the 1880s with eight novels in his famous Rougon-Macquart series. My four favorites are Nana (1880), about a prostitute; The Ladies’ Delight (1883), about a Paris department store that wreaks havoc on small retailers; Zola’s masterpiece Germinal (1885), about a mining town that experiences a dramatic strike; and The Masterpiece (1886), about a prototypical tortured artist.

Taking the time-travel route a year before Twain was Edward Bellamy and his utopian Looking Backward (1888), set in the year 2000. It was one of the 19th century’s three bestselling novels — after Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin (1852) and Lew Wallace’s Ben-Hur (1880), the latter of which I haven’t read so I can’t discuss it in this post. One of the many interesting things about Looking Backward (whose author was a cousin of “Pledge of Allegiance” creator Francis Bellamy) is that an early debit card appears in it!

Other notable novels of that decade included Thomas Hardy’s depressingly excellent The Mayor of Casterbridge (1886), Robert Louis Stevenson’s very influential Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde (also 1886), and William Dean Howells’ rags-to-riches-themed The Rise of Silas Lapham (1884).

An honorable mention goes to Billy Budd — which was started by Herman Melville in 1886, left unfinished at the time of his 1891 death, and finally published in 1924. Many consider it Melville’s second-best novel behind Moby-Dick.

Your favorite novels of the 1880s, including those I didn’t name?

My literary-trivia book is described and can be purchased here: Fascinating Facts About Famous Fiction Authors and the Greatest Novels of All Time.

In addition to this weekly blog, I write the award-winning “Montclairvoyant” topical-humor column for Baristanet.com. The latest piece — which again looks at the coronavirus pandemic’s effect on my town — is here.

I don’t think I’ve ever published a blog post on my birthday before, so I’ll “celebrate” by listing some novelists I love or like and how old they are. Why? Because it’s easier to make a list than to write a regular blog post of the kind I’ll resume next week. 🙂

I don’t think I’ve ever published a blog post on my birthday before, so I’ll “celebrate” by listing some novelists I love or like and how old they are. Why? Because it’s easier to make a list than to write a regular blog post of the kind I’ll resume next week. 🙂 “War is hell,” but it can also be almost an abstraction. Unless you’re directly affected, it might not seem quite as horrible as it actually is or as senseless as it usually is. Novels and other kinds of fiction can help.

“War is hell,” but it can also be almost an abstraction. Unless you’re directly affected, it might not seem quite as horrible as it actually is or as senseless as it usually is. Novels and other kinds of fiction can help. With the coronavirus wreaking havoc throughout the world — and American “leader” Donald Trump predictably responding to that pandemic in the most incompetent, empathy-lacking, and self-serving way imaginable — it would be understandable if book lovers would want to read only escapist fiction for a while. But if you’re a glutton for punishment, there are some very compelling novels out there with pandemic themes — many pessimistic about the situation and the reaction to it, others a bit more optimistic.

With the coronavirus wreaking havoc throughout the world — and American “leader” Donald Trump predictably responding to that pandemic in the most incompetent, empathy-lacking, and self-serving way imaginable — it would be understandable if book lovers would want to read only escapist fiction for a while. But if you’re a glutton for punishment, there are some very compelling novels out there with pandemic themes — many pessimistic about the situation and the reaction to it, others a bit more optimistic.

I’ve blogged about fiction written by

I’ve blogged about fiction written by  Have you ever read a novel that’s mostly low-key, subtle, understated, and even seemingly simple yet is compelling or charming or funny or emotionally wrenching or all of the above? Sure you have, and I have, too.

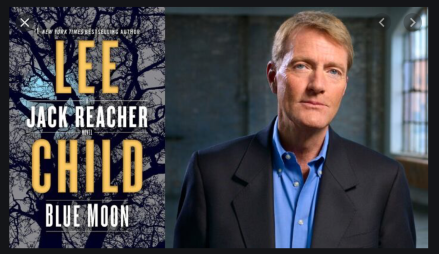

Have you ever read a novel that’s mostly low-key, subtle, understated, and even seemingly simple yet is compelling or charming or funny or emotionally wrenching or all of the above? Sure you have, and I have, too. After reading Lee Child’s latest Jack Reacher novel last week, I thought about how page-turning that series is and how it reflects our times. Heck, there’s an amazing/harrowing “fake news” reference near the end of that recent book, which chronicles Reacher’s battle against rival mobs that ruthlessly control a city.

After reading Lee Child’s latest Jack Reacher novel last week, I thought about how page-turning that series is and how it reflects our times. Heck, there’s an amazing/harrowing “fake news” reference near the end of that recent book, which chronicles Reacher’s battle against rival mobs that ruthlessly control a city. It’s anniversary time again! With a month-plus of 2020 “in the books,” I’d like to mention some of my favorite (not necessarily the best) novels that were published in 1970, 1920, 1870, and various other years ending in that big ol’ round number of zero. And then you can tell me some of your favorites.

It’s anniversary time again! With a month-plus of 2020 “in the books,” I’d like to mention some of my favorite (not necessarily the best) novels that were published in 1970, 1920, 1870, and various other years ending in that big ol’ round number of zero. And then you can tell me some of your favorites.