The first residents of what’s now the United States were Native Americans, but they haven’t often been first in the casts of novels. Still, there are a number of such characters, including more in recent years.

The first residents of what’s now the United States were Native Americans, but they haven’t often been first in the casts of novels. Still, there are a number of such characters, including more in recent years.

Their depictions, of course, have been all over the map — from stereotypical to fully three-dimensional. We might see the virulent discrimination against, and the poverty faced by, many Native Americans, or see some of them doing quite well. There are set-in-the-past depictions (including the genocide and otherwise horrific treatment at the hands of whites) and present-day portrayals. It helps when the author is partly or 100% Native American, but some authors with no such ancestry have done a reasonably good job with Native-American characters.

One Native-American author is Sherman Alexie, who I read for the first time last week with Reservation Blues. That novel chronicles the ups and downs of a Native-American rock band — with content also including a romance, mystical elements, interactions between Native Americans and whites, the effects of Christianity on the characters, struggles with alcoholism, and more.

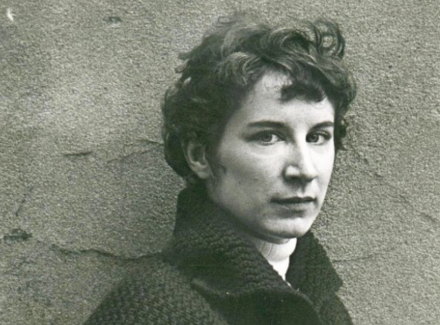

Another (partly) Native-American author is Louise Erdrich (pictured above). I read her novel The Painted Drum a few months ago, and it’s an absorbing tale of an important Ojibwe artifact and the impact it has on various characters.

Some novels with partly or 100% Native-American characters by authors who are not Native American? One famous example is One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest‘s Chief Bromden, who ends up in the book’s Oregon psychiatric hospital after descending into clinical depression partly caused by his father being humiliated at the hands of whites. He is one of the Ken Kesey novel’s three stars, along with Randle McMurphy and Nurse Ratched.

Then there’s The Charlestown Connection and other crime novels by Tom MacDonald featuring partly Native-American private sleuth Dermot Sparhawk.

The above books are basically set during the time they were written, but there are also a number of books by modern-day authors set in the long-ago past.

For instance, the star of Isabel Allende’s compelling Zorro — which takes place in the late 1700s and early 1800s — is of mixed Native-American and Spanish descent. Among that novel’s most interesting supporting characters are Native Americans: Zorro’s mother Toypurnia, his grandmother White Owl, and his lifelong best friend Bernardo — all well-drawn and non-stereotypical.

Two in the Field — the sequel to Darryl Brock’s riveting time-travel/baseball novel If I Never Get Back — takes 20th-century-protagonist Sam Fowler to the 1870s to search for his lost love Caitlin with the help of a Sioux guide. Sam even meets General Custer, against whom Native Americans won their famous (and rare) victory against the always-encroaching white menace.

They didn’t fare as well in Cormac McCarthy’s Blood Meridian, in which the vicious Glanton gang massacred many Native Americans and others during an 1849-50 rampage in the Southwest.

Literature fitting this topic written during the 1800s? Many Native Americans appear in James Fenimore Cooper’s five “Leatherstocking” novels — the most famous of which is The Last of the Mohicans. None of them are as prominently featured as white guy Natty Bumppo, but Natty’s friend Chingachgook is an important secondary character and several other Native Americans have noticeable supporting roles. While Cooper gets somewhat stereotypical at times, he was fairly enlightened for a white author of his era in decently depicting Native Americans.

“Injun Joe” of Mark Twain’s The Adventures of Tom Sawyer is more problematic. That half-Native American is portrayed as quite villainous, although Twain does offer some sense that one motive for the character’s actions is a desire to avenge the discrimination and ostracism he faced throughout his life.

Of course, some novels set in other countries also have indigenous characters — including the Eskimos of northern Canada in James Houston’s White Dawn and Mordecai Richler’s Solomon Gursky Was Here, Aboriginal Australians in novels such as Thomas Keneally’s The Chant of Jimmie Blacksmith, and so on.

I realized I’ve only touched the surface here. Your favorite novels that include Native-American or other indigenous characters?

Many of you know “Kat Lit,” a great/frequent/long-time poster here who hasn’t commented for a while. She tells me she has been dealing with a move and some health issues, says hello to everyone, misses everyone, and plans to return here when she can.

My literary-trivia book is described and can be purchased here: Fascinating Facts About Famous Fiction Authors and the Greatest Novels of All Time.

In addition to this weekly blog, I write the award-winning “Montclairvoyant” topical-humor column for Baristanet.com. The latest weekly piece — which compares the way my town coddles powerful developers with a neighboring town’s more community-minded approach — is here.

Have you ever read just one novel by an author — her or his most famous work — but then waited years to read some of their other, lesser-known books?

Have you ever read just one novel by an author — her or his most famous work — but then waited years to read some of their other, lesser-known books? Last week, I listed my favorite novels published between 2010 and 2019. This week, I’ll go back a decade to rank my favorite novels with 2000-to-2009 releases. Don’t worry, there’ll be no list of 1990s fiction in next week’s post… 🙂

Last week, I listed my favorite novels published between 2010 and 2019. This week, I’ll go back a decade to rank my favorite novels with 2000-to-2009 releases. Don’t worry, there’ll be no list of 1990s fiction in next week’s post… 🙂 As visitors to this blog know, I often write about novels that date back decades or centuries. But I also read some recent fiction, and thought I’d list my favorite novels published since 2010 — some literary, others mass-audience-oriented. Not necessarily the best novels of the past nine years (that’s so subjective anyway) but my personal favorites. Then I’ll ask for yours!

As visitors to this blog know, I often write about novels that date back decades or centuries. But I also read some recent fiction, and thought I’d list my favorite novels published since 2010 — some literary, others mass-audience-oriented. Not necessarily the best novels of the past nine years (that’s so subjective anyway) but my personal favorites. Then I’ll ask for yours! While there are still a few months left in 2019, I thought I’d write a post about this year’s round-number anniversaries of some major novels I’ve read.

While there are still a few months left in 2019, I thought I’d write a post about this year’s round-number anniversaries of some major novels I’ve read. As an adult who reads fiction, it’s interesting to occasionally encounter a novel in which the goings-on are viewed from a child character’s perspective.

As an adult who reads fiction, it’s interesting to occasionally encounter a novel in which the goings-on are viewed from a child character’s perspective. Last week’s post focused on characters who miss each other. This week, the focus will be on those who HATE each other.

Last week’s post focused on characters who miss each other. This week, the focus will be on those who HATE each other. I was away last week, and greatly missed my cat Misty. Which reminded me that reading about fictional characters who miss a living animal or a living person can be a very poignant thing. Hopefully followed by a happy reunion, but not always.

I was away last week, and greatly missed my cat Misty. Which reminded me that reading about fictional characters who miss a living animal or a living person can be a very poignant thing. Hopefully followed by a happy reunion, but not always. I was starting to read Alice Walker’s novel The Temple of My Familiar the morning of August 6 when I learned that literary great Toni Morrison had died the day before. So it seemed time to write a long-overdue piece about female authors of color.

I was starting to read Alice Walker’s novel The Temple of My Familiar the morning of August 6 when I learned that literary great Toni Morrison had died the day before. So it seemed time to write a long-overdue piece about female authors of color. Many novels of the past 50 years or so, including literary ones, have been fairly candid in their references to sexual matters. That’s the case with parts of John Irving’s In One Person, Zadie Smith’s On Beauty, Jonathan Franzen’s The Corrections, Alice Walker’s The Color Purple, Erica Jong’s Fear of Flying, Rita Mae Brown’s Rubyfruit Jungle, Philip Roth’s Portnoy’s Complaint, Jacqueline Susann’s Valley of the Dolls, and numerous other fiction books. (Fifty Shades of Grey? Haven’t read it.)

Many novels of the past 50 years or so, including literary ones, have been fairly candid in their references to sexual matters. That’s the case with parts of John Irving’s In One Person, Zadie Smith’s On Beauty, Jonathan Franzen’s The Corrections, Alice Walker’s The Color Purple, Erica Jong’s Fear of Flying, Rita Mae Brown’s Rubyfruit Jungle, Philip Roth’s Portnoy’s Complaint, Jacqueline Susann’s Valley of the Dolls, and numerous other fiction books. (Fifty Shades of Grey? Haven’t read it.)