Today is the first day of winter in the Northern Hemisphere, but it was also still autumn for a few hours. So, a two-faced day.

As in real life, some fictional characters also have two faces — offering different personas at different times and in different situations. This can be among the many building blocks involved in making a character complex, nuanced, and three-dimensional.

Perhaps the most literal depiction of a Janus-like character is the star of Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde. The duality in Robert Louis Stevenson’s 1886 novel happens when Jekyll, a basically good man with some repressed dark tendencies, takes a potion that turns him into the evil Hyde.

But things are usually somewhat more subtle when it comes to characters with binary tendencies.

For instance, the villainous Count Fosco can also be quite charming in Wilkie Collins’ 1860 classic The Woman in White.

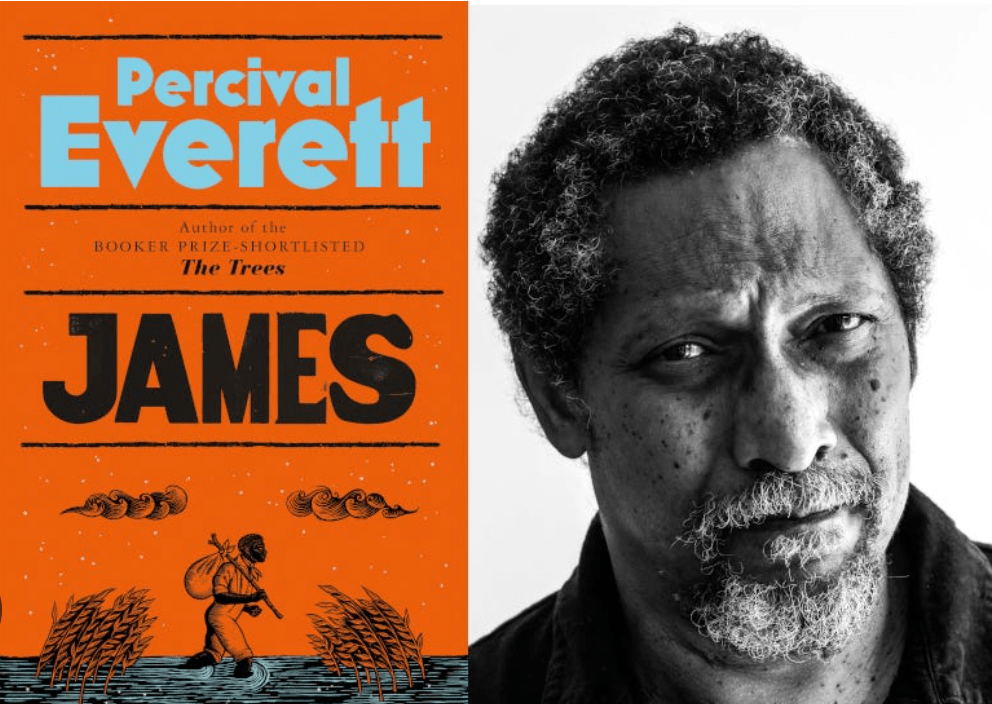

Much more recently, we have Percival Everett’s 2024 novel James, which reimagines Mark Twain’s Adventures of Huckleberry Finn from the vantage point of escaped slave Jim — after Twain mostly focused on Huck in his 1884 book. The duality here is that James, in a recognizable self-preservation maneuver, speaks in a different way (intellectually) to his fellow Black people than to white people (with whom he plays dumb). James, which I read last week, won the Pulitzer Prize for fiction earlier this year.

Jim’s dual persona reminds me of female characters who are smarter and/or more strategic than they let on. Daisy Buchanan of F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby (1925) would be one example.

Returning to contemporary literature, we have Val McDermid’s crime series about cold-case detective Karen Pirie. She is mostly tough while on the job — both with suspects and with the people (including sexist men) she works with — while Pirie’s more vulnerable side emerges in her personal life.

Then there are the characters who are warrior-like in battle even as they can have more-tender aspects when not fighting. Jamie Fraser of Diana Gabaldon’s Outlander series certainly has those two elements.

Sometimes, two parts of a personality exist more consecutively than simultaneously — as with young Neville Longbottom of J.K. Rowling’s Harry Potter series. He starts off bumbling and insecure, but eventually becomes quite courageous. Perhaps that arc is more maturity than duality.

Any comments about and/or examples of this topic?

Misty the cat says: “It’s the first day of winter. Autumn must still be around here somewhere.”

My comedic 2024 book — the part-factual/part-fictional/not-a-children’s-work Misty the Cat…Unleashed — is described and can be purchased on Amazon in paperback or on Kindle. It’s feline-narrated! (And Amazon reviews are welcome. 🙂 )

This 90-second promo video for the book features a talking cat: 🙂

I’m also the author of a 2017 literary-trivia book…

…and a 2012 memoir that focuses on cartooning and more, including many encounters with celebrities.

In addition to this weekly blog, I write the 2003-started/award-winning “Montclairvoyant” topical-humor column every Thursday for Montclair Local. The latest piece — which has a dystopian novel theme as it discusses 19 school-district jobs saved and 84 not saved (evoking George Orwell’s 1984) — is here.