In early 2016, I wrote about semi-autobiographical novels. Now that nearly 10 years have passed, I suppose it would be semi-okay to write about those books again — mentioning semi-autobiographical novels I’ve read since then or had read before then but didn’t mention in that previous post. So, with this semi-decent first paragraph nearly done, here goes:

As I wrote in ’16, semi-autobiographical novels “can be the best of both worlds for authors and their readers. That mix of memoir and fiction takes facts and embellishes them and/or dramatizes them and/or smooths them into more coherent form. A partly autobiographical approach also allows authors to potentially pen very heartfelt books — after all, they lived the emotions — and perhaps provides those writers with some mental therapy, too.” I also wrote that a semi-autobiographical novel is often, but of course not always, a debut novel — at least partly because that kind of book might be easier to write; the author can use aspects of her or his own past.

Back here in late 2025, I just read The Cat’s Table by Michael Ondaatje, whose 2011 coming-of-age novel was inspired to an extent by the author’s life and a ship voyage he took as a boy from his native Sri Lanka to rejoin his mother in England after his parents had separated several years earlier. A boy named…hmm…Michael. The Cat’s Table is another compelling book by The English Patient author, who went on to live in Canada.

Another semi-autobiographical/coming-of-age novel (those two things often go together) is Betty Smith’s 1943 bestseller A Tree Grows in Brooklyn — about a brainy girl (Francie) growing up in an impoverished urban family.

Then there’s Little Women by Louisa May Alcott, who loosely based her classic 1868-69 novel on herself and her three sisters.

A few decades earlier, Mary Shelley’s apocalyptic 1826 novel The Last Man featured three principal characters based on herself, her late husband Percy Bysshe Shelley, and their friend and fellow writer Lord Byron.

Aldous Huxley also used famous people as models for characters in his 1928 novel Point Counter Point — including himself, Nancy Cunard, D.H. Lawrence, and Katherine Mansfield.

The characters in Harper Lee’s To Kill a Mockingbird (1960) are somewhat modeled on the author’s father (attorney Atticus Finch in the novel), herself (Scout in the book) and Lee’s childhood friend Truman Capote (fictionally named Dill).

Kurt Vonnegut’s horrific World War II experiences were fuel for his sci-fi-infused 1969 novel Slaughterhouse-Five, and Jack Kerouac’s travel experiences provided fodder for his On the Road (1957).

Some of the semi-autobiographical novels mentioned in my 2016 post include James Baldwin’s Go Tell It on the Mountain, Ray Bradbury’s Dandelion Wine, Charlotte Bronte’s Villette, Rita Mae Brown’s Rubyfruit Jungle, Charles Bukowski’s Hollywood, Willa Cather’s My Antonia, Colette’s The Vagabond, Charles Dickens’ David Copperfield, E.L. Doctorow’s World’s Fair, Fyodor Dostoevsky’s The House of the Dead, George Eliot’s The Mill on the Floss, Nathaniel Hawthorne’s The Blithedale Romance, Zora Neale Hurston’s Their Eyes Were Watching God, Jack London’s Martin Eden, W. Somerset Maugham’s Of Human Bondage, Herman Melville’s Typee, L.M. Montgomery’s Emily trilogy, Sylvia Plath’s The Bell Jar, Erich Maria Remarque’s All Quiet on the Western Front, John Steinbeck’s East of Eden, and Amy Tan’s The Joy Luck Club.

Your thoughts about, and examples of, this topic?

Misty the cat says: “When Christmas-tree lights reflect off the window, it’s a pane in the grass.”

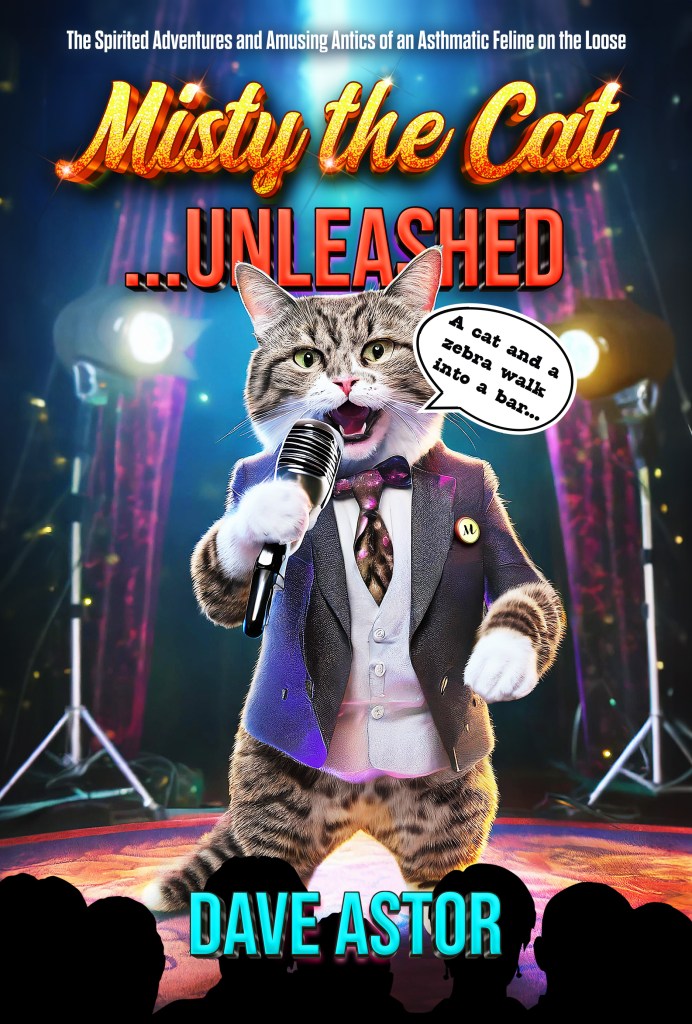

My comedic 2024 book — the part-factual/part-fictional/not-a-children’s-work Misty the Cat…Unleashed — is described and can be purchased on Amazon in paperback or on Kindle. It’s feline-narrated! (And Amazon reviews are welcome. 🙂 )

This 90-second promo video for the book features a talking cat: 🙂

I’m also the author of a 2017 literary-trivia book…

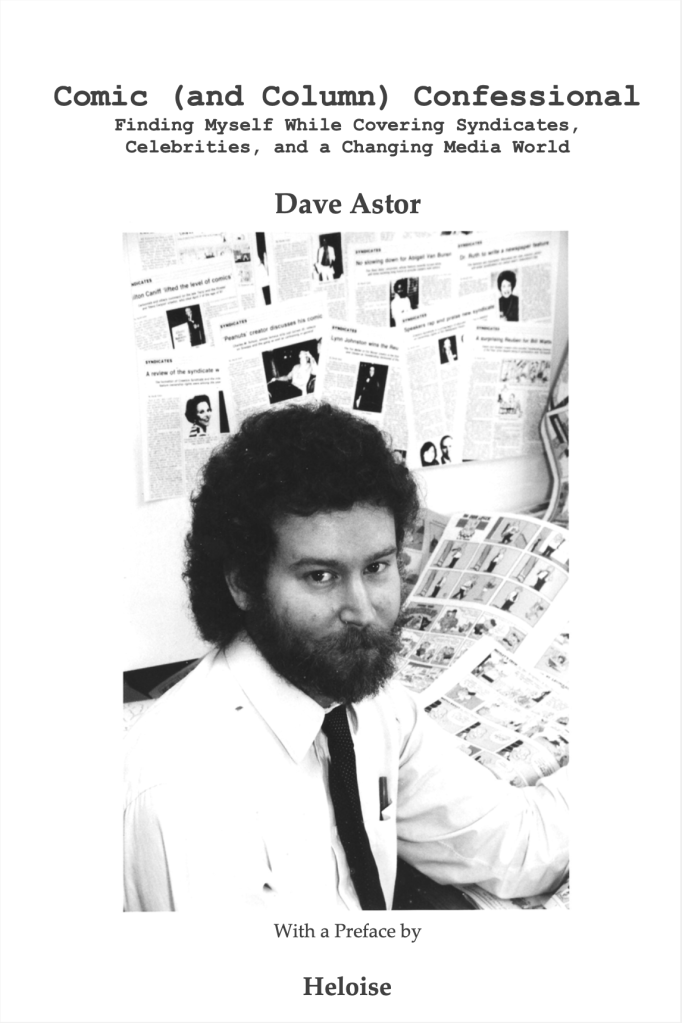

…and a 2012 memoir that focuses on cartooning and more, including many encounters with celebrities.

In addition to this weekly blog, I write the 2003-started/award-winning “Montclairvoyant” topical-humor column every Thursday for Montclair Local. The latest piece — which contains a tale of two meetings — is here.