Some fiction authors are rather formulaic while others vary their approach with almost every novel — and I like both kinds of writers.

Some fiction authors are rather formulaic while others vary their approach with almost every novel — and I like both kinds of writers.

Formulaic positives? There’s comfort in knowing (approximately) what to expect. Non-formulaic positives? The delicious element of surprise. If the authors are good, satisfaction is guaranteed either way.

Plus formulaic authors often offer enough differences in each of their books to satisfy a reader’s yen for variety, and non-formulaic authors frequently have recurring elements in their works. So there’s some blurring between the two “camps.”

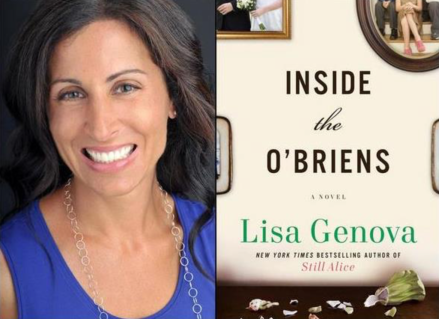

I recently finished my third Lisa Genova novel, Left Neglected. As with her also-great Still Alice and Inside the O’Briens, a character faces a major neurological challenge — with the story told from the perspective of that character and Genova covering all the medical and emotional bases. But there are variations: A different kind of neurological challenge in each of the three novels, whether ultimately fatal or not. Female protagonists in Still Alice and Left Neglected, a male protagonist in Inside the O’Briens. Affluent families in Still Alice and Left Neglected, a less-affluent family in Inside the O’Briens. Adult children in Still Alice and Inside the O’Briens, younger kids in Left Neglected. Etc.

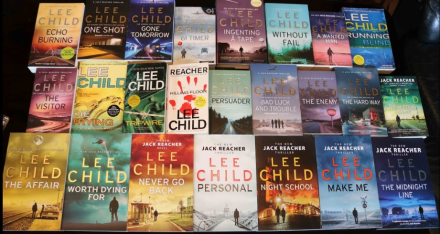

Lee Child of Jack Reacher series fame also has his formula: The roaming Jack goes to a new place, trouble arises, Reacher deals with that trouble, Jack leaves town. But then there’s the variety: a new locale in almost every book, different kinds of trouble in almost every book, new supporting characters in almost every book, and so on. The 24th Reacher novel, Blue Moon, was released late last month, and I have no doubt it will be another Child page-turner when I get to it.

Excellent authors of thriller, detective, or mystery series frequently fit into the formulaic but not totally formulaic camp. Agatha Christie, Janet Evanovich, Sue Grafton, Tony Hillerman, Martin Cruz Smith, and many others.

In each of his 20 Rougon-Macquart novels published between 1871 and 1893, Emile Zola featured one or more members of those R-M families and usually offered an overarching theme: alcoholism in The Drinking Den, retailing in The Ladies’ Delight, mining in Germinal, art in The Masterpiece, rail travel in The Beast in Man, etc. So, those compelling Zola books were similar in a way, yet the characters of course had varied personalities and fates, and the aforementioned themes were also quite varied.

Some authors who often avoid a formula from novel to novel?

Margaret Atwood is certainly one. She’s expertly handled contemporary fiction (such as Cat’s Eye), historical fiction (Alias Grace), and of course “speculative” fiction (including The Handmaid’s Tale and its recent sequel The Testaments). But there are certain commonalities amid Atwood’s genre-jumping, most notably a feminist sensibility and other kinds of social awareness.

We also have J.K. Rowling. After she finished her seven blockbuster Harry Potter books, she wrote the decidedly non-magical/very sobering novel The Casual Vacancy. Then Rowling switched things up again with a crime series (four so far) starring private investigator Cormoran Strike. She skillfully nailed each of the three genres — and, while her approach in each is different, there are common elements such as deep sympathy for the underdog and a keen awareness of evil in the world.

Aldous Huxley is best known for his dystopian sci-fi classic Brave New World, but he also penned un-BNW-like novels such as Point Counter Point — a societal chronicle reminiscent of some 19th-century British literary fiction. Huxley displayed enough versatility to almost seem like different writers.

Authors you feel fit into either the formulaic or non-formulaic categories?

My literary-trivia book is described and can be purchased here: Fascinating Facts About Famous Fiction Authors and the Greatest Novels of All Time.

In addition to this weekly blog, I write the award-winning “Montclairvoyant” topical-humor column for Baristanet.com. The latest weekly piece — which covers overly aggressive driving and many other topics — is here.

One of the many jaw-dropping spectacles offered by the dumpster fire of the corrupt and incompetent Trump administration is seeing how low Rudy Giuliani (pictured above) can go.

One of the many jaw-dropping spectacles offered by the dumpster fire of the corrupt and incompetent Trump administration is seeing how low Rudy Giuliani (pictured above) can go. In the case of many novels, readers basically know the general parameters of what will happen. In the case of many other novels, the plot destination is a complete or near-complete unknown (unless a review or too-talkative friend gives things away 🙂 ). Either type of novel has the potential to be compelling.

In the case of many novels, readers basically know the general parameters of what will happen. In the case of many other novels, the plot destination is a complete or near-complete unknown (unless a review or too-talkative friend gives things away 🙂 ). Either type of novel has the potential to be compelling. The first residents of what’s now the United States were Native Americans, but they haven’t often been first in the casts of novels. Still, there are a number of such characters, including more in recent years.

The first residents of what’s now the United States were Native Americans, but they haven’t often been first in the casts of novels. Still, there are a number of such characters, including more in recent years. Have you ever read just one novel by an author — her or his most famous work — but then waited years to read some of their other, lesser-known books?

Have you ever read just one novel by an author — her or his most famous work — but then waited years to read some of their other, lesser-known books? Last week, I listed my favorite novels published between 2010 and 2019. This week, I’ll go back a decade to rank my favorite novels with 2000-to-2009 releases. Don’t worry, there’ll be no list of 1990s fiction in next week’s post… 🙂

Last week, I listed my favorite novels published between 2010 and 2019. This week, I’ll go back a decade to rank my favorite novels with 2000-to-2009 releases. Don’t worry, there’ll be no list of 1990s fiction in next week’s post… 🙂 As visitors to this blog know, I often write about novels that date back decades or centuries. But I also read some recent fiction, and thought I’d list my favorite novels published since 2010 — some literary, others mass-audience-oriented. Not necessarily the best novels of the past nine years (that’s so subjective anyway) but my personal favorites. Then I’ll ask for yours!

As visitors to this blog know, I often write about novels that date back decades or centuries. But I also read some recent fiction, and thought I’d list my favorite novels published since 2010 — some literary, others mass-audience-oriented. Not necessarily the best novels of the past nine years (that’s so subjective anyway) but my personal favorites. Then I’ll ask for yours! While there are still a few months left in 2019, I thought I’d write a post about this year’s round-number anniversaries of some major novels I’ve read.

While there are still a few months left in 2019, I thought I’d write a post about this year’s round-number anniversaries of some major novels I’ve read. As an adult who reads fiction, it’s interesting to occasionally encounter a novel in which the goings-on are viewed from a child character’s perspective.

As an adult who reads fiction, it’s interesting to occasionally encounter a novel in which the goings-on are viewed from a child character’s perspective.