Sometimes, authors dazzle with their debut novels. Mary Shelley and Frankenstein. Emily Bronte and Wuthering Heights. Carson McCullers and The Heart Is a Lonely Hunter. Ralph Ellison and Invisible Man. Arundhati Roy and The God of Small Things. Zadie Smith and White Teeth. Etc.

But more frequently there’s somewhat of a learning curve for authors, which is totally natural — and totally the topic of this post.

I came to this topic via the work of Stephenie Meyer, three of whose novels I recently read in reverse order: first The Chemist (2016), then The Host (2008), and then Twilight (2005). Twilight was of course Meyer’s mega-bestselling debut featuring a teen human and teen vampire who fall in love. An interesting take on the vampire genre that held my interest even as it was too often written in a pedestrian way. Published three years later, The Host turned out to be a fascinating sci-fi story — and more skillfully crafted. Finally, The Chemist thriller about a hunted female ex-government agent was full of superb prose and dialogue. Meyer’s wordsmithing arc was impressive.

It all reminded me a bit of J.K. Rowling’s progression. The first Harry Potter novel was compelling and tons of fun as the author did her world-building, even as the writing itself was not super-scintillating. But Rowling’s prose and dialogue got better and better as her next six wizard-realm books emerged, and continued in that direction with the skillfully written The Casual Vacancy and the riveting crime series starring private investigators Cormoran Strike and Robin Ellacott.

Both Rowling and Meyer can be rather long and wordy in their more recent offerings, but I’m here for it.

Going much further back in time, I liked the feminist idea of Jack London’s early novel A Daughter of the Snows, but the dialogue was laughable and the prose clunky. One year later, London’s pitch-perfect The Call of the Wild was released. I don’t know what writing elixir the author imbibed during those 12 months, but I want it. 🙂

F. Scott Fitzgerald’s college-set debut novel This Side of Paradise is quite uneven, only hinting at the greatness of The Great Gatsby published just five years later.

John Steinbeck’s debut novel Cup of Gold was an okay, rather conventional pirate novel before much of his later fiction became light years better — including, of course, his masterpiece The Grapes of Wrath.

Willa Cather’s first two novels — Alexander’s Bridge and O Pioneers! — exhibited some authorial growing pains before they were followed by her absorbing The Song of the Lark and then the masterful My Antonia.

Dan Brown’s early-career novel The Da Vinci Code was VERY popular and quite ingenious in its way but even more awkwardly written than Stephenie Meyer’s Twilight. I never read Brown again, but I assume his writing improved?

Any comments about, or examples of, this theme?

Misty the cat asks: “How am I supposed to shovel this stuff without opposable thumbs?”

My comedic 2024 book — the part-factual/part-fictional/not-a-children’s-work Misty the Cat…Unleashed — is described and can be purchased on Amazon in paperback or on Kindle. It’s feline-narrated! (And Amazon reviews are welcome. 🙂 )

This 90-second promo video for the book features a talking cat: 🙂

I’m also the author of a 2017 literary-trivia book…

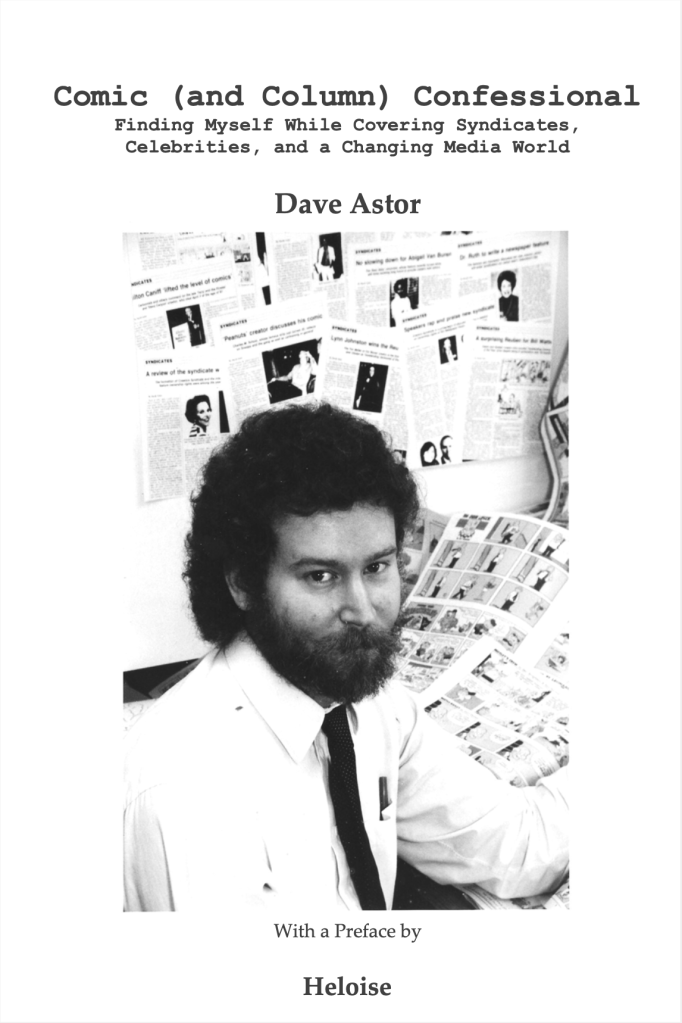

…and a 2012 memoir that focuses on cartooning and more, including many encounters with celebrities.

In addition to this weekly blog, I write the 2003-started/award-winning “Montclairvoyant” topical-humor column every Thursday for Montclair Local. The latest piece — which has “no appeal” appeal — is here.