March is my birthday month, so I thought I’d list and discuss famous March-born authors I’ve read at least one book by.

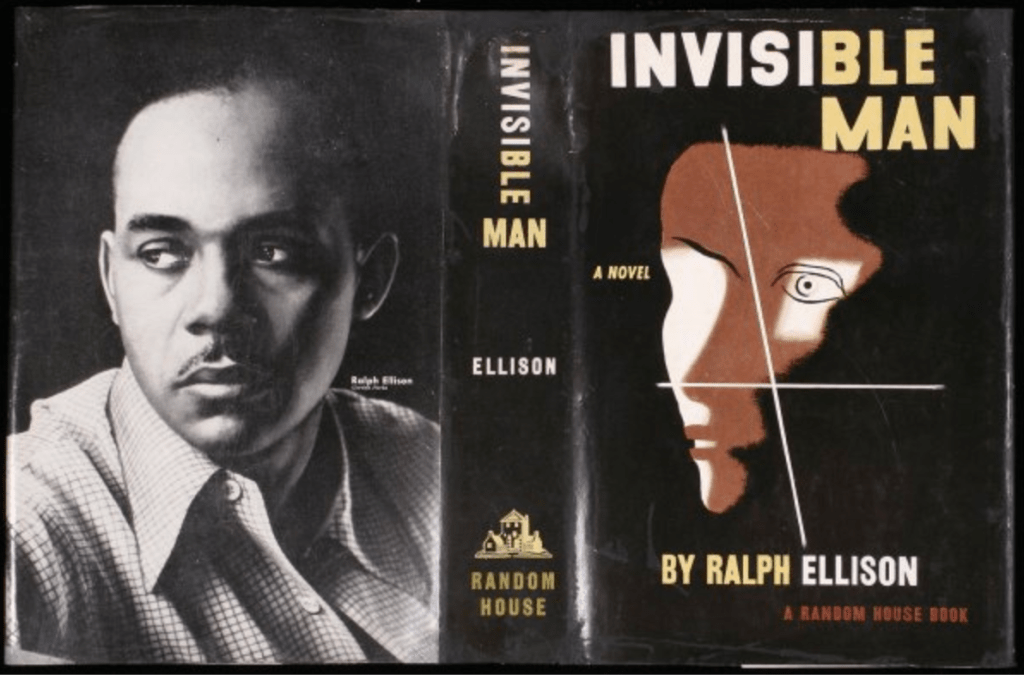

March 1: Ralph Ellison (1913-1994). He of course wrote Invisible Man, which says more about racism and other aspects of United States life than most other novels have ever done.

March 2: John Irving (1942-). I’ve read four of his novels, with The Cider House Rules my favorite. He’s really skilled at combining the quirky and the profound, with social commentary also a big part of the mix.

March 2: Peter Straub (1943-2022). His intricate Ghost Story was quite good but could have been somewhat shorter.

March 4: Khaled Hosseini (1965-). His debut novel The Kite Runner is very compelling, although one loses a lot of sympathy for protagonist Amir after his nasty act of betrayal.

March 6: Gabriel Garcia Marquez (1927-2014). I’ve read five of his novels — One Hundred Years of Solitude is obviously his best — and he was masterful at mixing magic realism, political elements, pathos, romance, and more.

March 8: Jeffrey Eugenides (1960-). His Middlesex novel memorably depicts an intersex character while also having plenty to say about family dynamics, the immigrant experience, etc.

March 11: Douglas Adams (1952-2001). His The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy is an enjoyable read, though I think somewhat overrated.

March 12: Jack Kerouac (1922-1969). I also think On the Road is overrated, but it does say a lot about wanderlust, The Beat Generation, and the culture of its time.

March 13: Viet Thanh Nguyen (1971-). His novel The Sympathizer and its sequel The Committed — both starring an unnamed part-Vietnamese spy — offer an impressive page-turning amalgam of war commentary, multiculturalism, humor, and more.

March 13: Tad Williams (1957-). His Tailchaser’s Song is an epic fantasy novel starring…cats.

March 18: John Updike (1932-2009). The only novel of his I’ve read is Rabbit, Run, and, while I admired the writing, I was not a big fan of the book’s brew of white-male angst and misogyny.

March 19: Philip Roth (1933-2018). This author can also be annoying amid the great writing chops, but the neurotic Portnoy’s Complaint is funny as hell.

March 20: Lois Lowry (1937-). Her young-adult dystopian novel The Giver is quite good, and its sequels aren’t bad, either.

March 20: Louis Sachar (1954-). His eccentric Holes is one of the better YA novels I’ve read, including its feminist and antiracist aspects.

March 22: Louis L’Amour (1908-1988). He’s best known for western novels, but his Soviet Union-set Last of the Breed is pretty exciting, too.

March 22: James Patterson (1947-). Tried just one of his novels; wasn’t a fan. Also not a fan of his “factory” approach of using a team of co-authors to churn out book after book.

March 23: Julia Glass (1956-). I’ve read her very good Three Junes, which, as the title implies, has an interesting/interrelated three-part format.

March 25: Flannery O’Connor (1925-1964). She’s best-known for chilling short stories such as “A Good Man Is Hard to Find,” but also wrote the intriguing novel Wise Blood.

March 27: Julia Alvarez (1950-). Her novel In the Time of the Butterflies is a gripping piece of historical fiction about sisters bravely opposing the former Dominican Republic dictatorship.

March 28: Russell Banks (1940-2023). I’ve only read his Rule of the Bone, a gritty look at characters living in the underbelly of the U.S. and Jamaica.

March 28: Mario Vargas Llosa (1936-2025): His offbeat Aunt Julia and the Scriptwriter definitely held my interest.

March 31: Nikolai Gogol (1809-1852). His novel Dead Souls is an eye-opener, and his short story “The Overcoat” is a classic tale that influenced great Russian writers later in the 19th century. (Some sources say Gogol was born on April 1.)

March 31: Marge Piercy (1936-). Her Woman on the Edge of Time is an original combination of social justice and science fiction writing.

March 31: Judith Rossner (1935-2005). Her Looking for Mr. Goodbar was quite a sensation in its 1970s time.

Notable March-born writers I’ve read who are known for work other than novels include children’s book author Dr. Seuss, playwright Tennessee Williams, and poets Robert Frost and Elizabeth Barrett Browning, among others.

Any thoughts on this post, or examples of other March-born writers you’ve read?

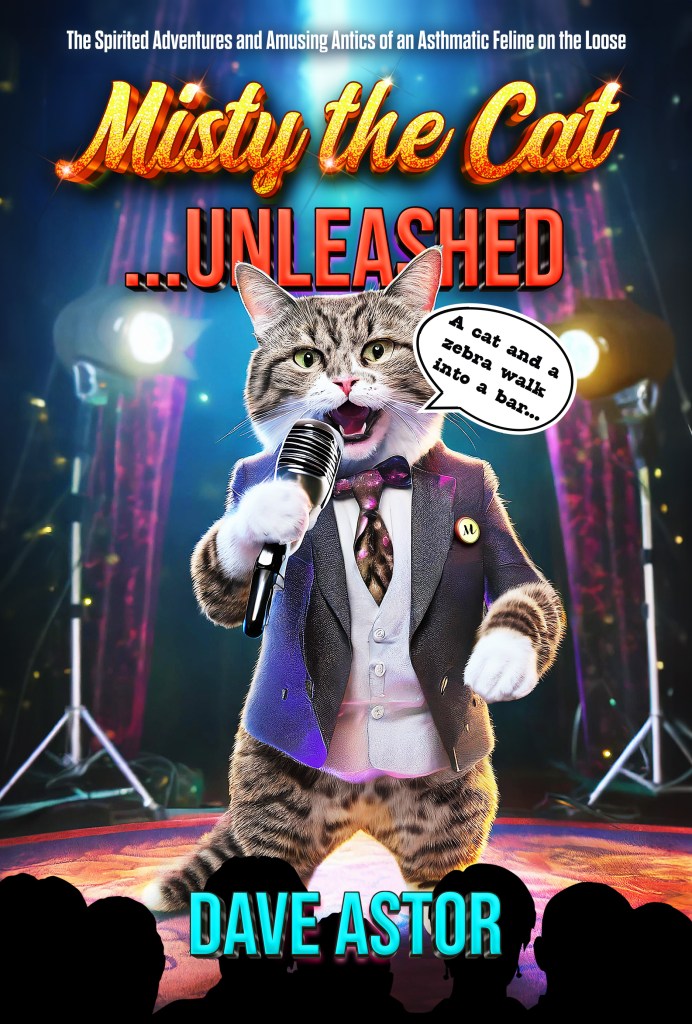

As he runs in the direction of NYC, Misty asks: “How can cats live in ‘the city that never sleeps’?”

My comedic 2024 book — the part-factual/part-fictional/not-a-children’s-work Misty the Cat…Unleashed — is described and can be purchased on Amazon in paperback or on Kindle. It’s feline-narrated! (And Amazon reviews are welcome. 🙂 )

This 90-second promo video for the book features a talking cat: 🙂

I’m also the author of a 2017 literary-trivia book…

…and a 2012 memoir that focuses on cartooning and more, including many encounters with celebrities.

In addition to this weekly blog, I write the 2003-started/award-winning “Montclairvoyant” topical-humor column every Thursday for Montclair Local. The latest piece — containing commentary on a big snowstorm and all kinds of controversial news in my town — is here.