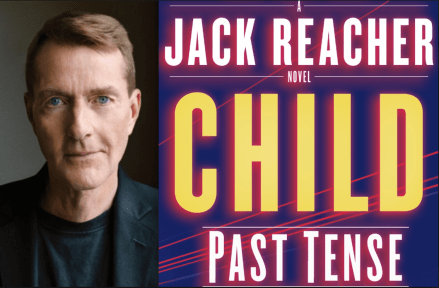

When I recently finished Past Tense, the latest page-turner starring Jack Reacher, I realized that I had now read 20 of Lee Child’s 23 great Reacher books. Which made me wonder, have I ever read that many novels by any other author?

So I scoured my list of books read, and my memory, to try to figure out which authors I had spent the most time with during my life. Of course, some writers pen longer novels than others, but I was looking strictly for number of books.

My first thought turned to Charles Dickens, because I took a college literature course in which the students read nothing but him. It turned out that I’ve read 14 Dickens novels, with a few of them perused pre- and post-college. Among my favorites? David Copperfield and The Pickwick Papers.

But I’ve actually read more books by Stephen King, not surprising given how prolific a writer he is. Fifteen of his novels, with my favorites Misery and From a Buick 8, among others. Actually, Misery might go under the category of “most intense” rather than a number-one favorite.

John Steinbeck? Thirteen of his novels read, with The Grapes of Wrath and East of Eden the ones I liked best. Also 13 for Colette, with my favorites The Vagabond and Claudine at School.

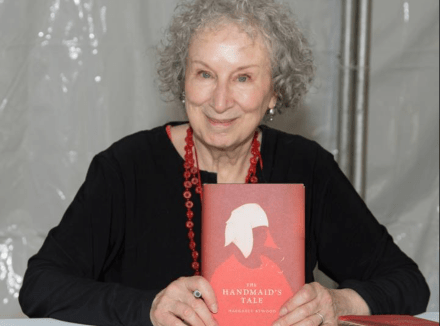

I’ve read all 12 of Willa Cather’s novels, enjoying My Antonia and The Song of the Lark the most. Twelve for Margaret Atwood, too, with my preferences including The Robber Bride and Alias Grace. And 12 for L.M. Montgomery, including my favorite-ever YA novel — Anne of Green Gables — as well as various Anne sequels and the sublime stand-alone novel The Blue Castle.

With 12 a popular number here, I’ll add J.K. Rowling. I’ve read her seven Harry Potter books as well as The Casual Vacancy, and am now in the middle of the fourth title (Lethal White) in her excellent crime series written under the Robert Galbraith alias. I’ve also read Harry Potter and the Cursed Child, but that’s a theater piece. I’m just doing novels here, not plays, short-story collections, nonfiction, etc.

Some of my other most-read authors (and some of my favorite novels of theirs) include Alexandre Dumas, 10 books (The Count of Monte Cristo and Georges); Sir Walter Scott, 10 (Old Mortality and The Heart of Midlothian); Martin Cruz Smith, 10 (Gorky Park and Rose); Jack London, 9 (Martin Eden and The Sea-Wolf); Cormac McCarthy, 9 (Suttree and Blood Meridian); Fannie Flagg, 8 (Fried Green Tomatoes at the Whistle Stop Café and The All-Girl Filling Station’s Last Reunion); and six authors with seven apiece: Henry James (The Portrait of a Lady and The American), Barbara Kingsolver (The Poisonwood Bible and Prodigal Summer), Herman Melville (Moby-Dick and Pierre), Erich Maria Remarque (Arch of Triumph and The Night in Lisbon), Mark Twain (Adventures of Huckleberry Finn and A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur’s Court), and Emile Zola (Germinal and The Beast in Man).

Then there’s Jane Austen, 6 (Persuasion and Pride and Prejudice); and these novelists with five apiece: Honoré de Balzac (Old Goriot and Eugenie Grandet), James Fenimore Cooper (The Deerslayer and The Last of the Mohicans), Fyodor Dostoyevsky (Crime and Punishment and The Brothers Karamazov), George Eliot (Daniel Deronda and The Mill on the Floss), Aldous Huxley (Brave New World and Point Counter Point), W. Somerset Maugham (Of Human Bondage and The Razor’s Edge), Leo Tolstoy (War and Peace and Anna Karenina), Jules Verne (Around the World in Eighty Days and Journey to the Center of the Earth), H.G. Wells (The Time Machine and The First Men in the Moon), and Edith Wharton (The House of Mirth and The Age of Innocence).

Looking over my list so far, I’m embarrassed that there are no authors of color listed, though Dumas and Colette had some black ancestry. But I’ve read anywhere from one to four novels apiece by writers (my favorite books of theirs in parentheses) such as Isabel Allende (The House of the Spirits), James Baldwin (Go Tell It On the Mountain), David Bradley (The Chaneysville Incident), Octavia Butler (Kindred), Junot Diaz (The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao), Ralph Ellison (Invisible Man), Buchi Emecheta (Second Class Citizen), Alex Haley (Roots), Zora Neale Hurston (Their Eyes Were Watching God), Jhumpa Lahiri (The Lowland), Gabriel García Márquez (One Hundred Years of Solitude), Terry McMillan (Waiting to Exhale), Toni Morrison (Beloved), Walter Mosley (Devil in a Blue Dress), Arundhati Roy (The God of Small Things), Zadie Smith (White Teeth), Wole Soyinka (The Interpreters), Alice Walker (The Color Purple), and Richard Wright (Native Son), among various others.

Well, I guess I’ve never read more books by a writer other than Lee Child. He and his Jack Reacher character are highly addicting.

Which novelists have you read the most, in number of books?

My literary-trivia book is described and can be purchased here: Fascinating Facts About Famous Fiction Authors and the Greatest Novels of All Time.

In addition to this weekly blog, I write the award-winning “Montclairvoyant” topical-humor column for Baristanet.com. The latest weekly piece — about the 2020 Democratic presidential field and a hometown astronaut’s unfortunate association with Trump at the State of the Union address — is here.