A current major issue in my town of Montclair, New Jersey, is a massive school-budget deficit. As I continued to write about that each week in my “Montclairvoyant” topical-humor column, thoughts came to mind about fictional people facing debt and related financial troubles — a situation that provides much dramatic fodder while often evoking sympathy for those money-challenged characters.

Not knowing in advance that it would fit this topic, I happened last week to read a Richard Paul Evans novel called The Walk in which Seattle ad executive Alan Christoffersen loses his home, his car, and most of his other possessions because of huge medical bills for his paralyzed-in-an-accident wife McKale, being cheated by his work partner, and other reasons.

When reading about any character in fiscal peril, we wonder how they will react and what the ultimate outcome for them will be. In Evans’ 2009 novel, a despairing Alan ends up starting a long walk to Key West, Florida…nearly 3,500 miles away!

The pricey and problematic health-care system in the U.S. — the world’s only “developed” country without some form of government-run national insurance for all — also takes a huge financial toll on Shep Knacker when his wife Glynis becomes ill in (Ms.) Lionel Shriver’s compelling part-satirical novel So Much for That (2010).

Moving from the 21st-century United States to 19th-century France, we have Honore de Balzac’s 1837 novel Cesar Birotteau — whose Parisian title character is a successful shop owner and deputy mayor who becomes bankrupt after getting manipulated into property speculation. He spends the rest of the book on a mission to restore his honor by trying to pay off his debt.

A later French novel, Emile Zola’s The Drinking Den (1877), features another initially successful businessperson: Gervaise Macquart, who manages to open her own laundry through very hard work. She is happily married until her husband’s life spirals downward after he falls from a roof. Coupeau’s descent drags the family into poverty and alcoholism.

In-between those books came Gustave Flaubert’s 1857 novel Madame Bovary, in which the adulterous title character gets into serious debt spending on luxuries. When the debt is called in and can’t be paid, Emma Bovary decides to…

Over in 19th-century England, there was Charles Dickens’ also-published-in-1857 novel Little Dorrit — whose title character (first name Amy) was born and grows up in a debtors’ prison where her father William has been incarcerated. Partly inspired by Dickens’ childhood.

Back in France, Guy de Maupassant’s classic 1884 short story “The Necklace” is about a woman who loses a glittery borrowed necklace and goes into years of life-ruining debt after paying for a replacement. The tale has one of the most famous surprise endings in literature.

Authors themselves have of course also experienced money troubles. For instance, Sir Walter Scott in later life tried to frantically write his way out of debt after a banking crisis caused the collapse of a printing business in which the Scottish author had a large financial stake.

Also later in life, Mark Twain filed for bankruptcy after years of investing heavily in a mechanical typesetter that didn’t catch on. He survived financially and paid off debt by giving up his ornate Hartford, Connecticut, mansion and later embarking on a worldwide speaking tour.

Your thoughts about, and examples of, this theme?

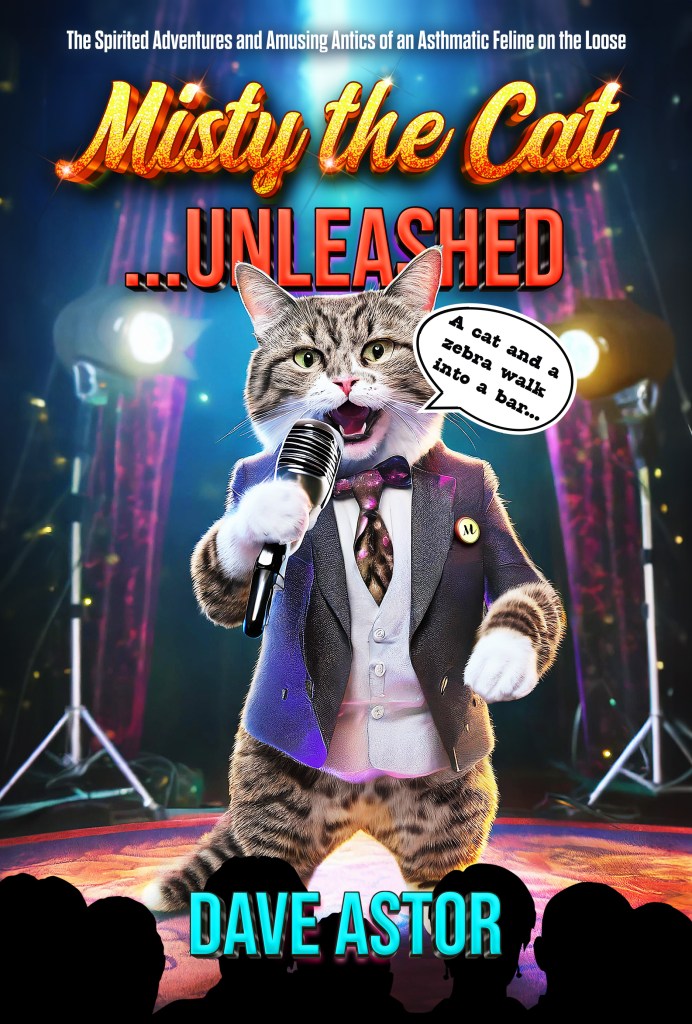

Misty the cat says: “I didn’t know my apartment complex was zoned for a car dealership.”

My comedic 2024 book — the part-factual/part-fictional/not-a-children’s-work Misty the Cat…Unleashed — is described and can be purchased on Amazon in paperback or on Kindle. It’s feline-narrated! (And Amazon reviews are welcome. 🙂 )

This 90-second promo video for the book features a talking cat: 🙂

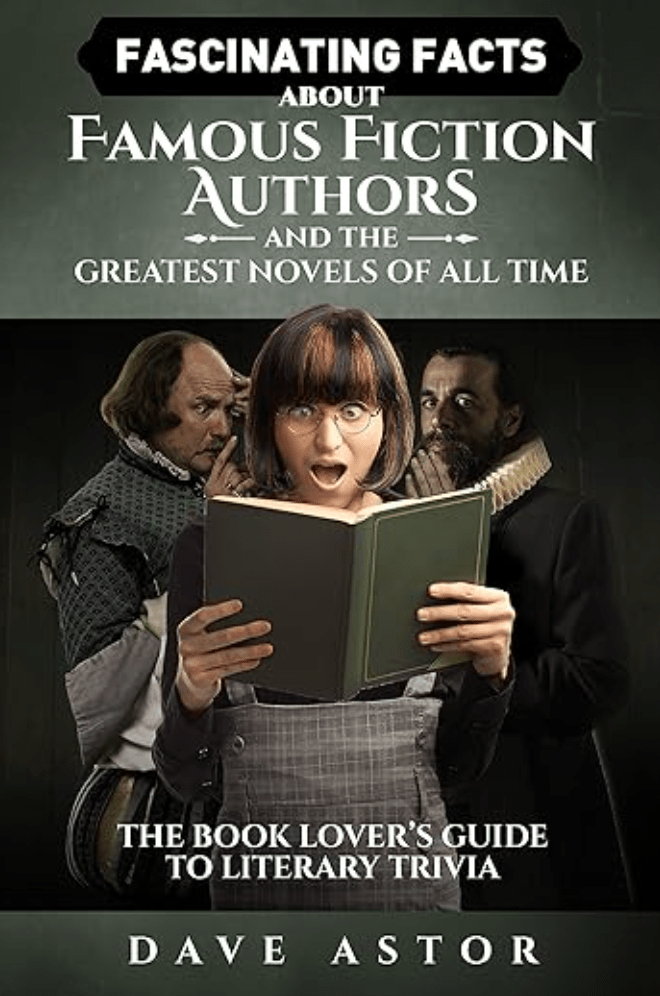

I’m also the author of a 2017 literary-trivia book…

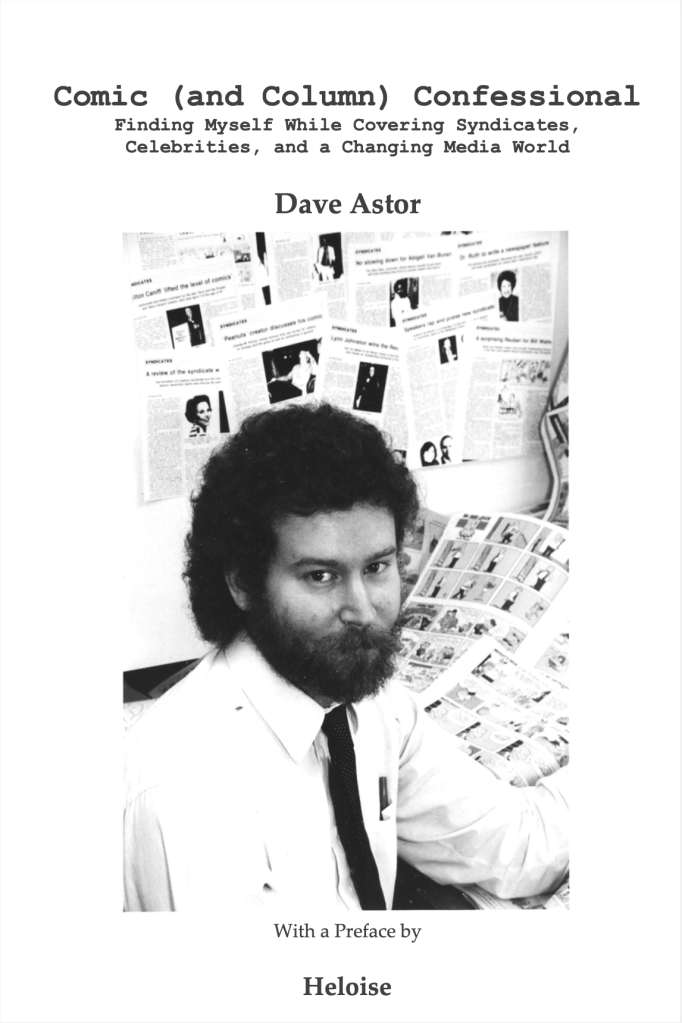

…as well as a 2012 memoir that focuses on cartooning and more, and includes many encounters with celebrities.

In addition to this weekly blog, I write the 2003-started/award-winning “Montclairvoyant” topical-humor column every Thursday for Montclair Local. The latest piece — about my local Township Council’s welcome vote to support a proposed state bill to protect immigrants from the Trump regime — is here.