A street in Antigua, Guatemala, that has nothing to do with the topic of this literature post. 🙂 (Photo by me on January 8.)

Glad to be back! I missed writing a post last week because of a trip I took with my wife Laurel and younger daughter Maria to Guatemala, where Maria was born. A memorable visit that included stops in Guatemala City, Tikal, Antigua, Panajachel, and Guatemala City again.

Today, as I do every January, I’m going to mention well-known novels — many of which I’ve read, some of which I haven’t — reaching major round-number anniversaries. So, in 2026, novels published in 2001 are turning 25, 1976-released books are turning 50, 1926 novels are turning 100, etc.

The first 2001 novel that came to mind was Richard Russo’s riveting Pulitzer Prize winner Empire Falls, set in a Maine blue-collar town.

Released that year, too, was Jonathan Franzen’s The Corrections, about a couple and their three adult children. I liked it better than the author’s much-touted Freedom, though that 2010 novel was pretty good as well.

Also, Yann Martell’s Life of Pi, which features a boy stranded on a boat with a tiger after a shipwreck; Sue Monk Kidd’s The Secret Life of Bees, which has a lot to say about female relationships as well as racism; Ann Patchett’s Bel Canto, a riveting look at a mass-hostage situation; Amy Tan’s The Bonesetter’s Daughter, about a Chinese-American woman and her immigrant mother; Ian McEwan’s Atonement, which I found both compelling and annoying; John Grisham’s semi-autobiographical A Painted House; Neil Gaiman’s fantasy tour de force American Gods; and Jasper Fforde’s clever The Eyre Affair.

Kristin Hannah’s peak as an author was yet to arrive, but her somewhat-early-in-career 2001 novel Summer Island was quite absorbing as it focused on a fraught mother-daughter relationship and rapprochement.

In the series realm, Diana Gabaldon’s fifth Outlander novel (The Fiery Cross) and Lee Child’s fifth Jack Reacher novel (Echo Burning) came out 25 years ago.

The year 2001 also saw the publication of Carlos Ruiz Zafon’s The Shadow of the Wind and Dennis Lehane’s Mystic River, neither of which I’ve read.

In 1976, the most famous release was Alex Haley’s Roots, which was of course the multi-generational American slavery saga about Kunta Kinte and his descendants.

There was also Margaret Atwood’s third novel Lady Oracle, about a woman with multiple identities; and Marge Piercy’s Woman on the Edge of Time, a sci-fi-ish work whose lower-income protagonist is unjustly committed to a psychiatric institution.

Notable 1976 books I haven’t read include Anne Rice’s debut novel Interview with the Vampire and Judith Guest’s made-into-a-memorable-movie Ordinary People.

Exactly a century ago — 1926 — saw the appearance of Ernest Hemingway’s The Sun Also Rises, which I thought was good not great.

An underrated classic that year was L.M. Montgomery’s The Blue Castle, about a young woman who gets very bad news that turns out to be very good news.

There was also Colette’s The Last of Cheri, the sequel to the 1920 Cheri novel about the relationship between a younger man and older woman; and My Mortal Enemy, one of Willa Cather’s lesser works.

Well-known 1926 novels I haven’t read include Agatha Christie’s The Murder of Roger Ackroyd and Upton Sinclair’s Oil!

Published 150 years ago, in 1876: Mark Twain’s iconic The Adventures of Tom Sawyer, about a rascally boy and his friend Huckleberry Finn.

That year also saw the release of Daniel Deronda, George Eliot’s final novel and one of her best. Its title character, who discovers he’s Jewish, interacts with some very memorable people.

In addition, there was Thomas Hardy’s not-famous-but-interesting The Hand of Ethelberta.

Two 1826 highlights were Mary Shelley’s apocalyptic, late-21st-century-set The Last Man and James Fenimore Cooper’s The Last of the Mohicans that unfolds in 1757 during the French and Indian War. Two novels with “Last” in the title that lasted.

And in 1726, 300 years ago, Jonathan Swift’s iconic Gulliver’s Travels was published!

Any thoughts on the novels I discussed? Any other titles you’d like to mention from those anniversary years? (I’m sure I missed some.)

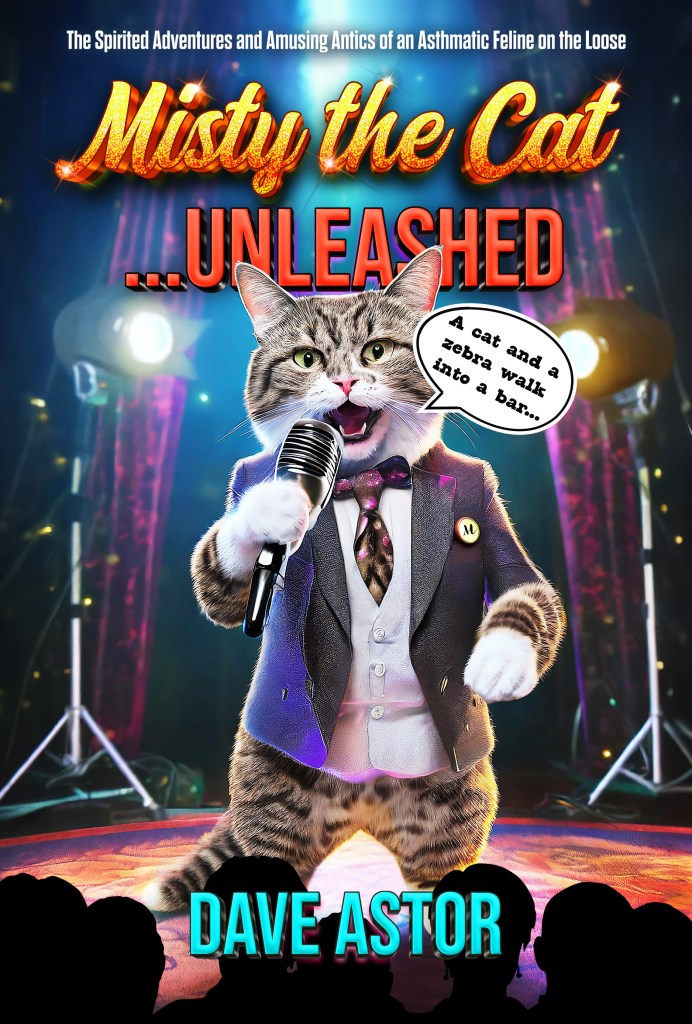

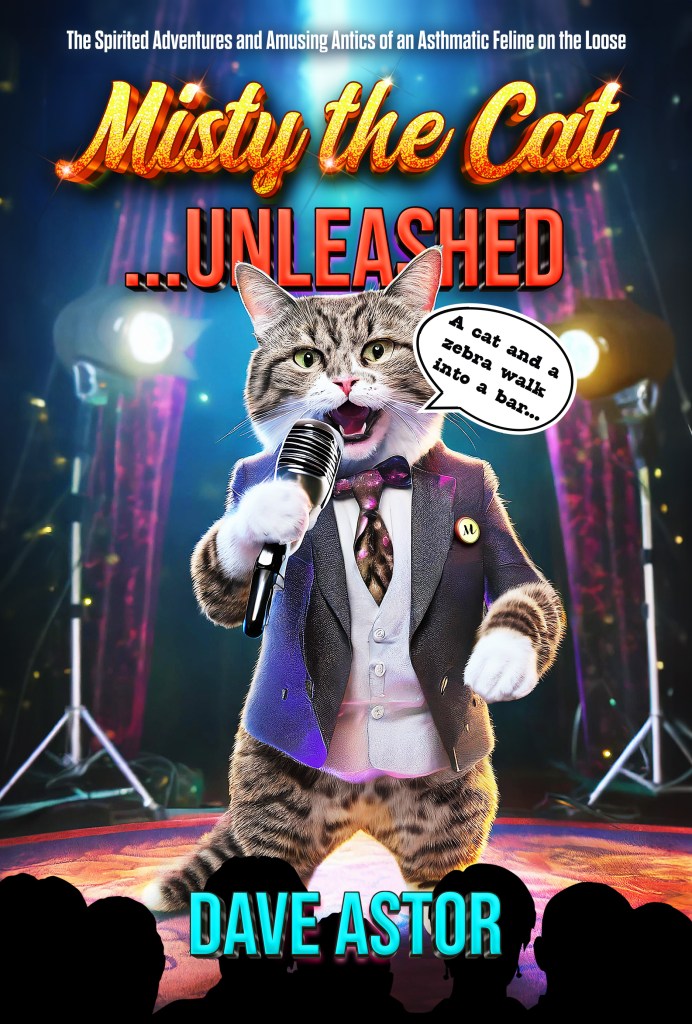

Misty the cat says: “Tofu falling from the sky was not on my 2026 bingo card.”

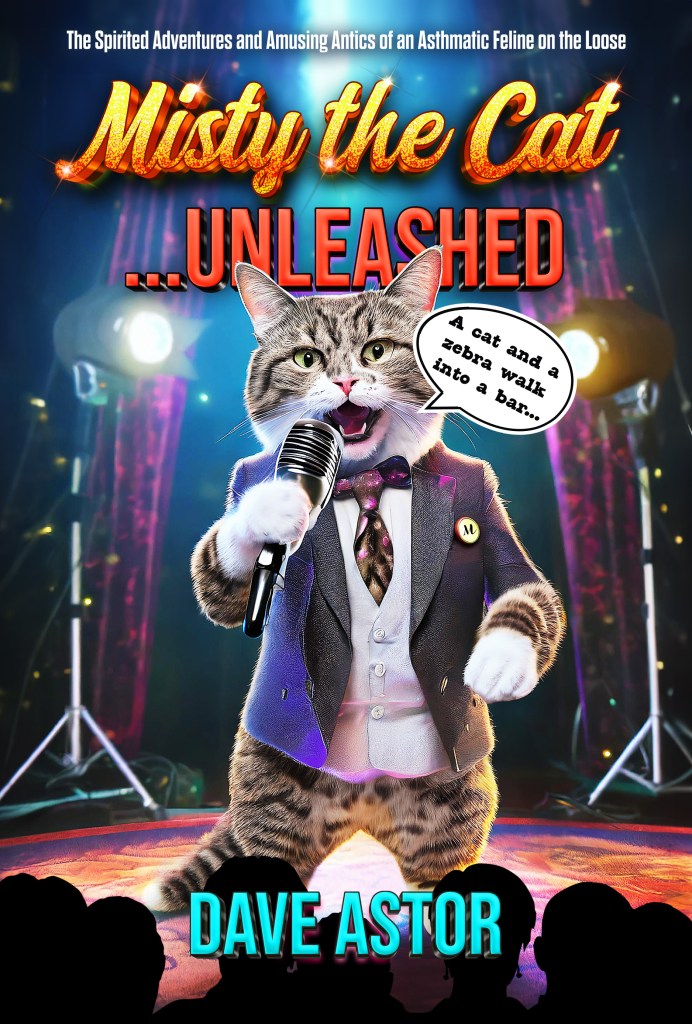

My comedic 2024 book — the part-factual/part-fictional/not-a-children’s-work Misty the Cat…Unleashed — is described and can be purchased on Amazon in paperback or on Kindle. It’s feline-narrated! (And Amazon reviews are welcome. 🙂 )

This 90-second promo video for the book features a talking cat: 🙂

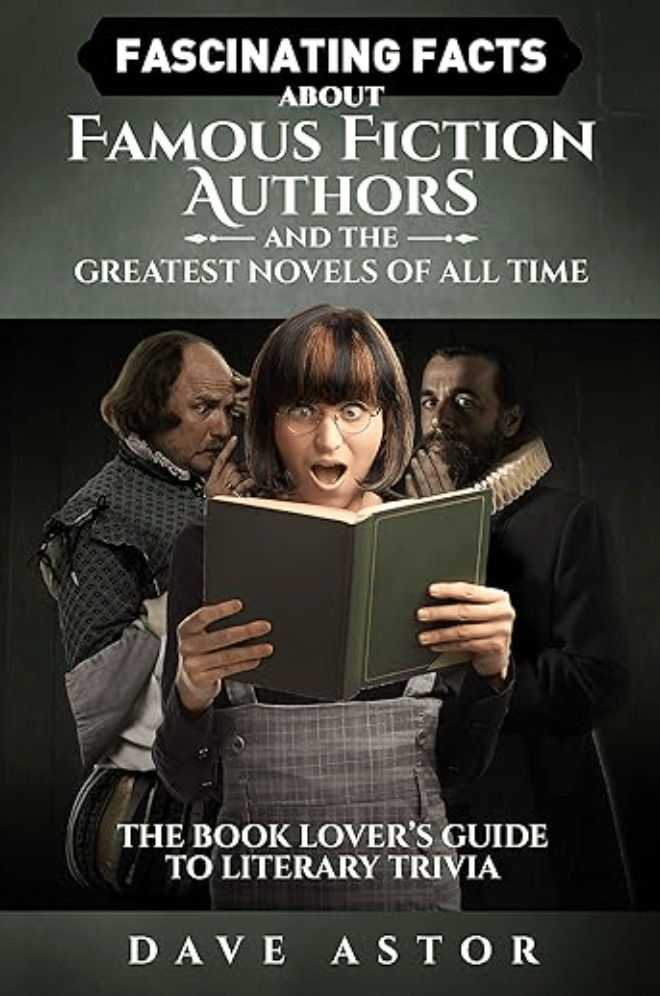

I’m also the author of a 2017 literary-trivia book…

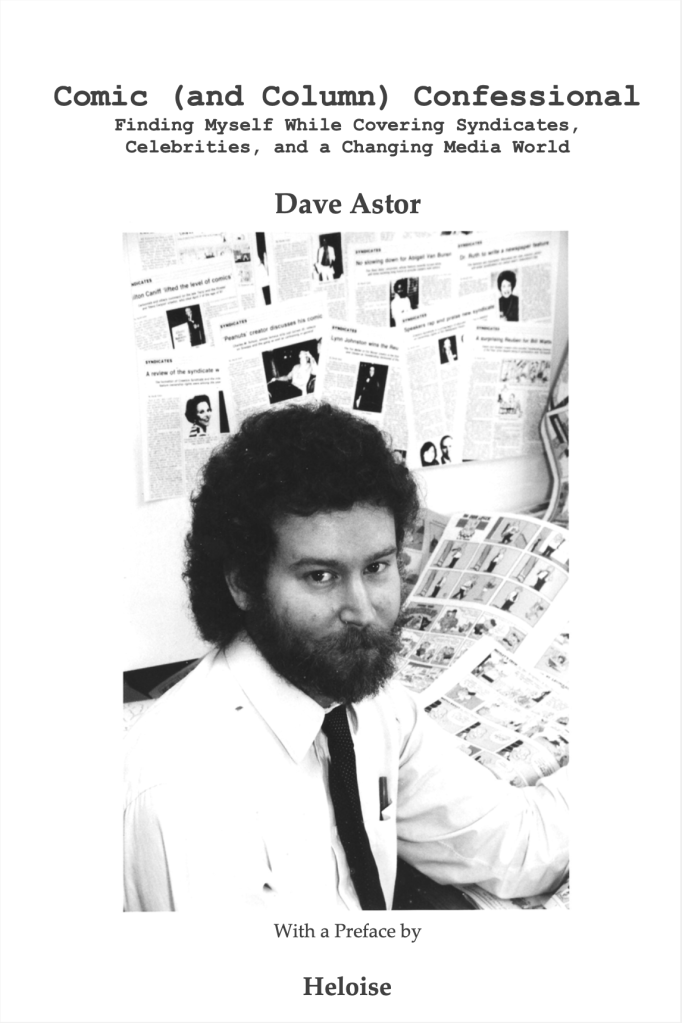

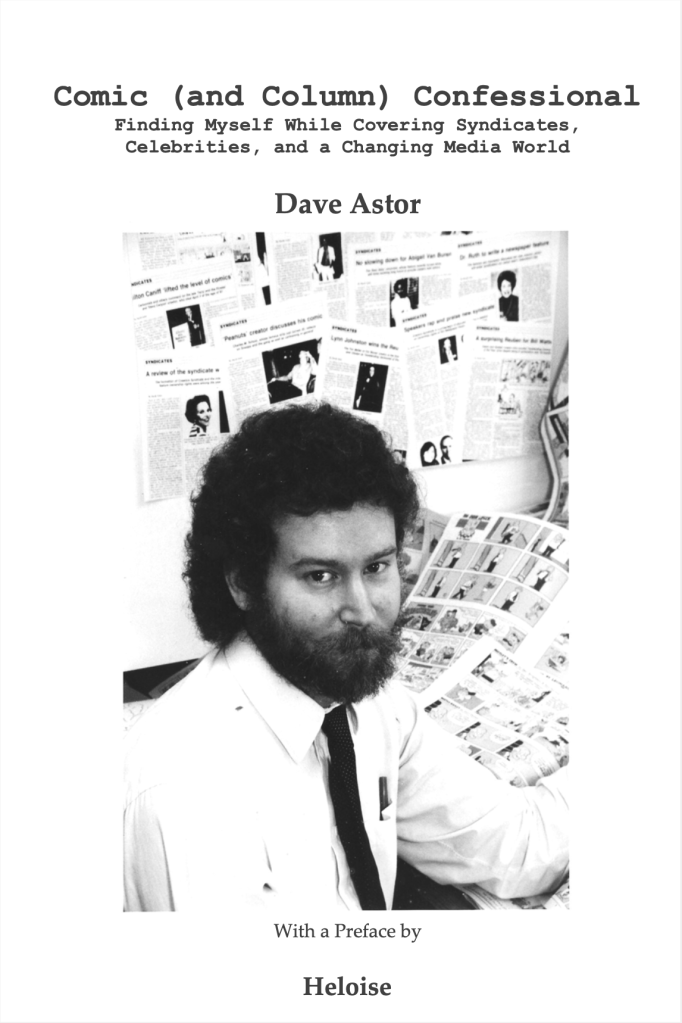

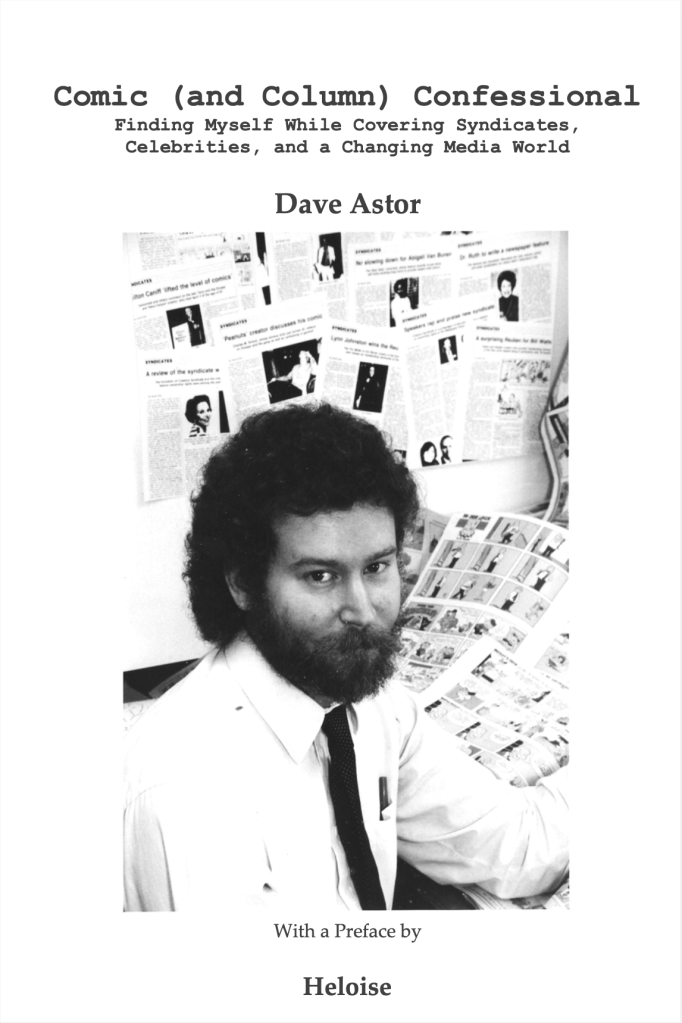

…and a 2012 memoir that focuses on cartooning and more, including many encounters with celebrities.

In addition to this weekly blog, I write the 2003-started/award-winning “Montclairvoyant” topical-humor column every Thursday for Montclair Local. The latest piece — about two meetings, a local anti-ICE protest, and more — is here.