From the trailer for 1959’s film version of Our Man in Havana.

I should have posted this “Spies in Literature” piece last Sunday the 7th in honor of Agent 007 James Bond, but I hadn’t yet finished the novel that inspired what you’re about to read.

That interesting 1958 book is Graham Greene’s Our Man in Havana, and while its protagonist James Wormold is not a typical spy (he’s a vacuum-cleaner salesperson who reluctantly accepts recruitment as an agent), he nonetheless ends up in espionage.

Wormold is a satirical creation — the reports he submits to headquarters are pure fiction — but many other spies in literature are quite serious characters even if some humor might occasionally enter the mix. These secret agents can make for compelling reading as they get into adventures, risk their lives, save lives, end lives, do undercover work for good or evil patrons, inhabit a milieu of geopolitical machinations, etc.

I initially mentioned James Bond, and have seen a couple of movies starring him, but must admit I’ve never read any of the Ian Fleming novels that inspired the long-running 007 film franchise.

But I have enjoyed a handful of other books with spy characters. One author quite famous for that genre is John le Carré, whose The Russia House (1989) is the only novel of his I’ve read. It unfolds near the end of the Cold War — just before the breakup of the Soviet Union — and is pretty absorbing.

The Cold War of course has inspired many a spy novel, which could include Viet Tranh Nguyen’s The Sympathizer if the Vietnam War is considered partly a manifestation of that era’s United States/Soviet Union tensions. His seriocomic 2015 novel — set in 1975 and subsequent years — is told by an unnamed North Vietnamese mole in the South Vietnamese army who remains embedded in a South Vietnamese immigrant community in the U.S. Its sequel, The Committed, was published in 2021.

Obviously, not all espionage novels have a Cold War connection. For instance, James Fenimore Cooper’s 1821-released The Spy (hmm…I wonder what its title character is 🙂 ) takes place during the American Revolutionary War of several decades earlier.

And in the Harry Potter series, Severus Snape is a spy of sorts — and the most complex and morally ambivalent character in those seven J.K. Rowling novels.

I’ve barely touched the surface here, as I haven’t read that many books with secret-agent characters. Any thoughts on spies in literature? Your favorite characters and novels in this realm?

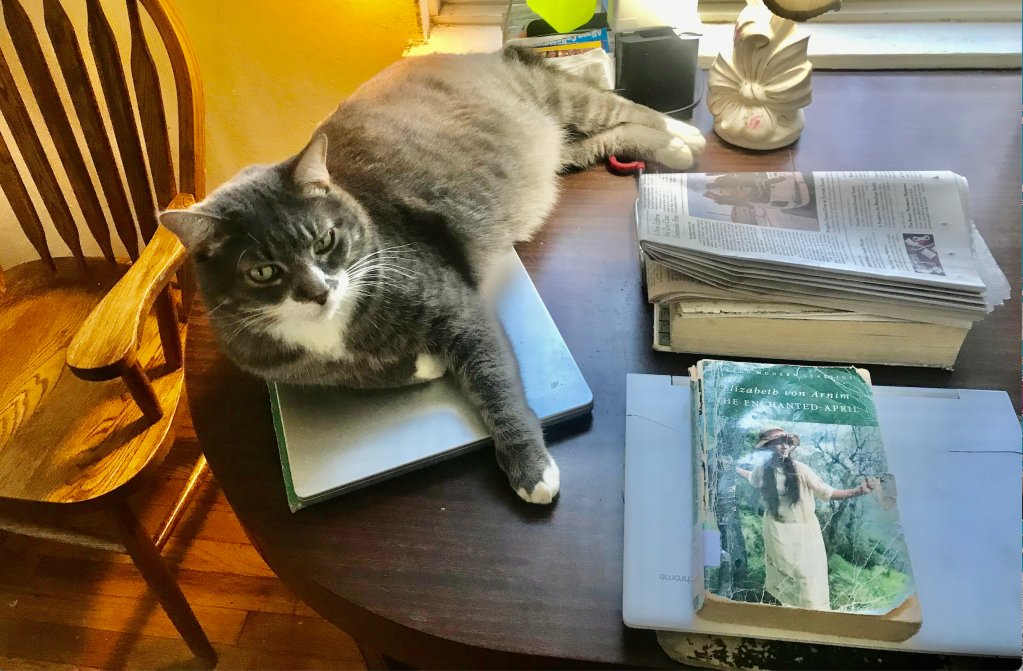

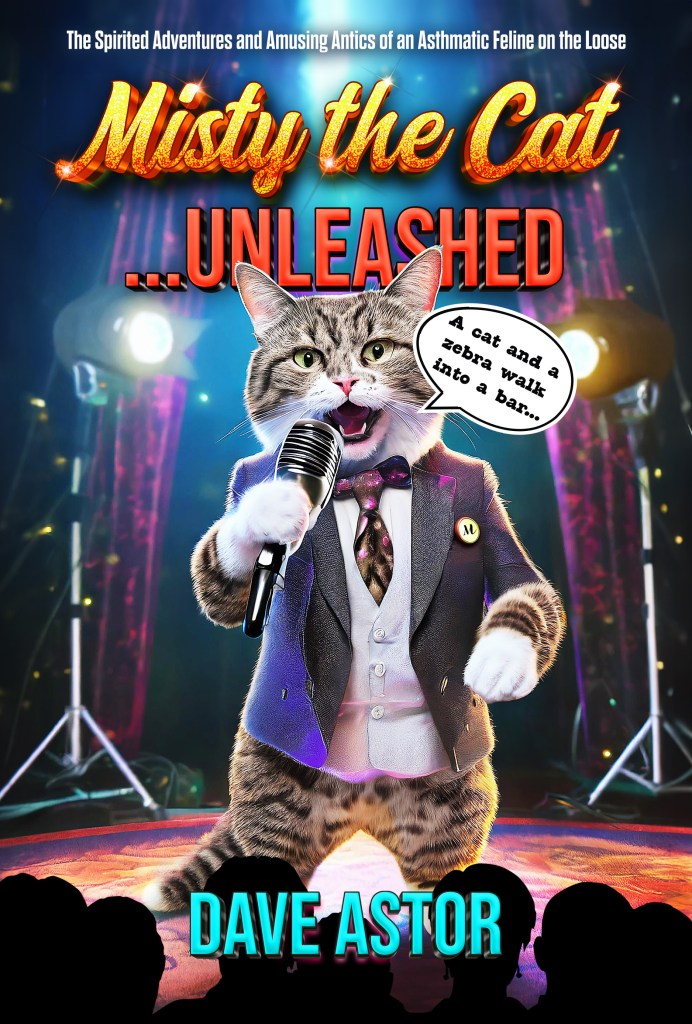

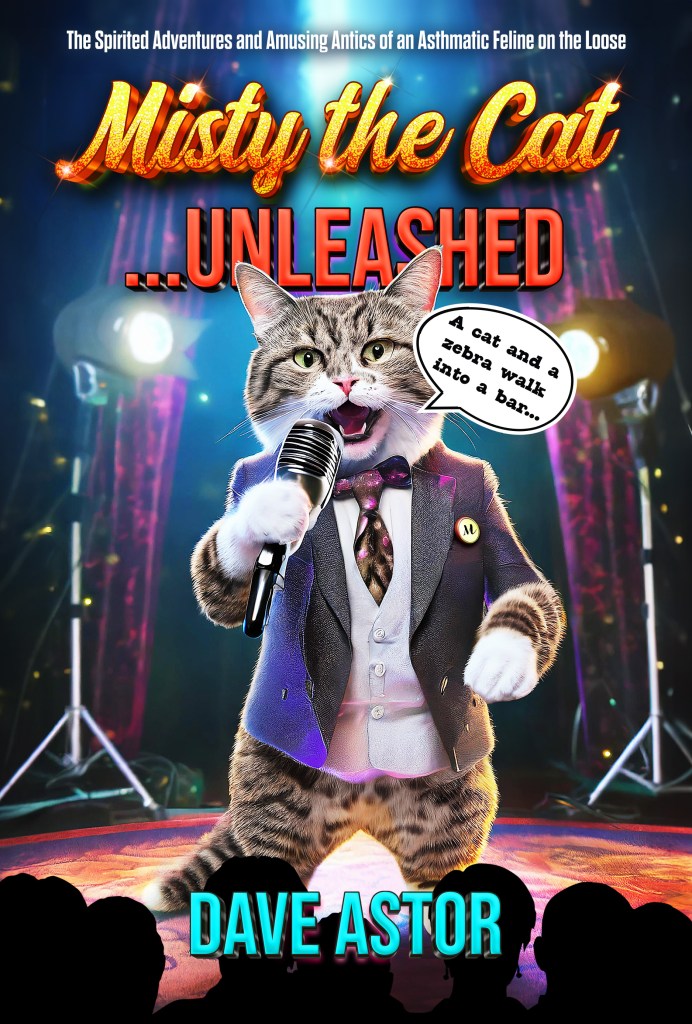

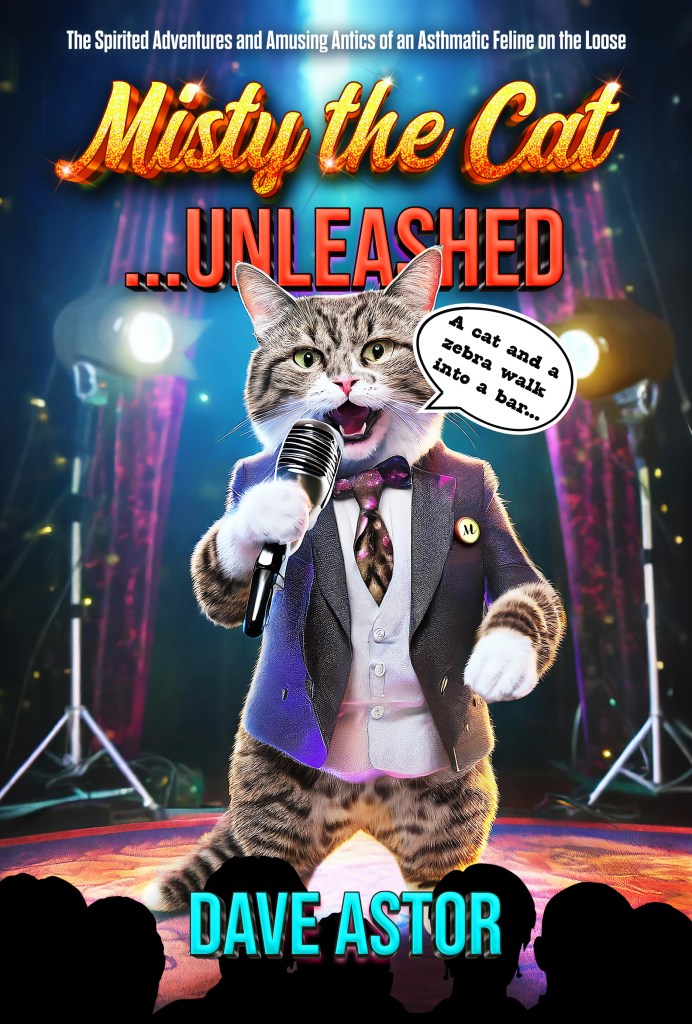

Misty the cat says: “I see thorns but not birds, so ‘The Thorn Birds’ novel doesn’t exist.”

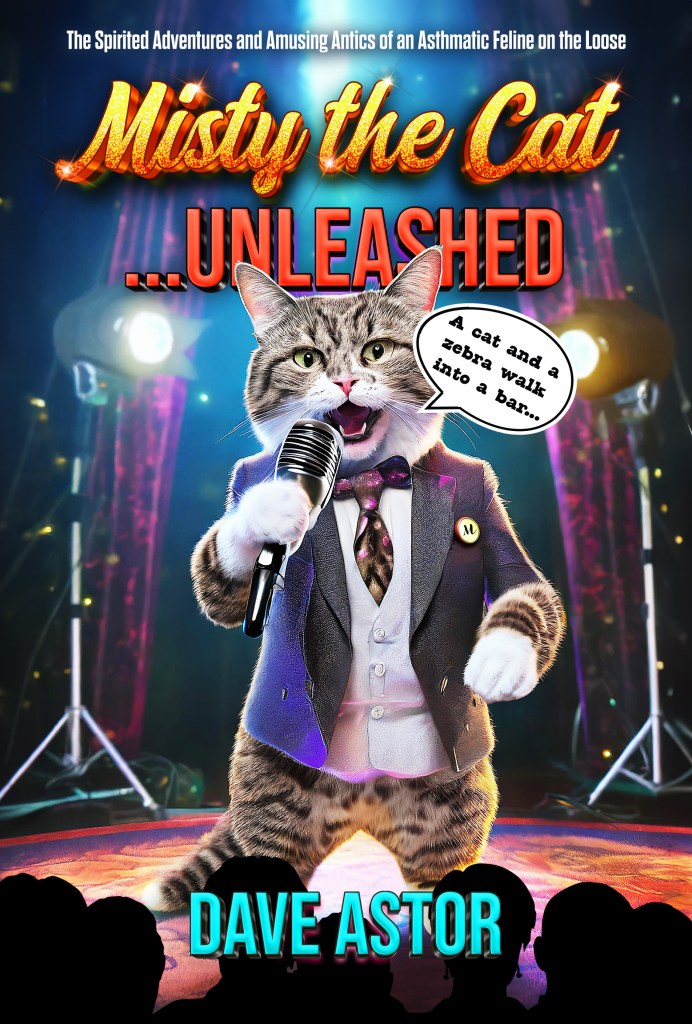

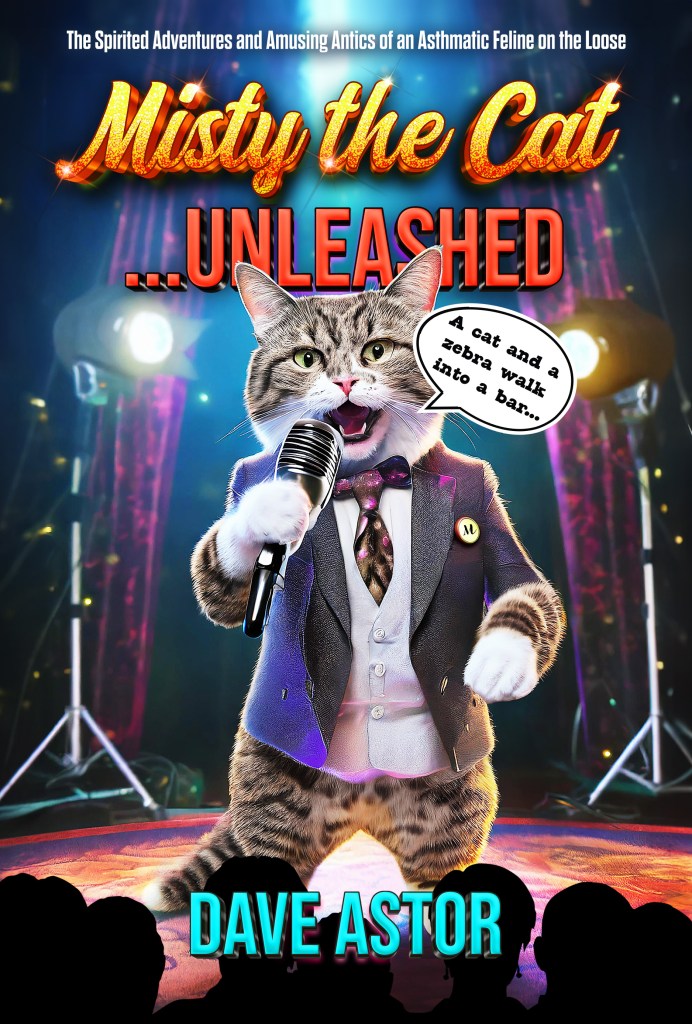

My comedic 2024 book — the part-factual/part-fictional/not-a-children’s-work Misty the Cat…Unleashed — is described and can be purchased on Amazon in paperback or on Kindle. It’s feline-narrated! (And Misty says Amazon reviews are welcome. 🙂 )

This 90-second promo video for the book features a talking cat: 🙂

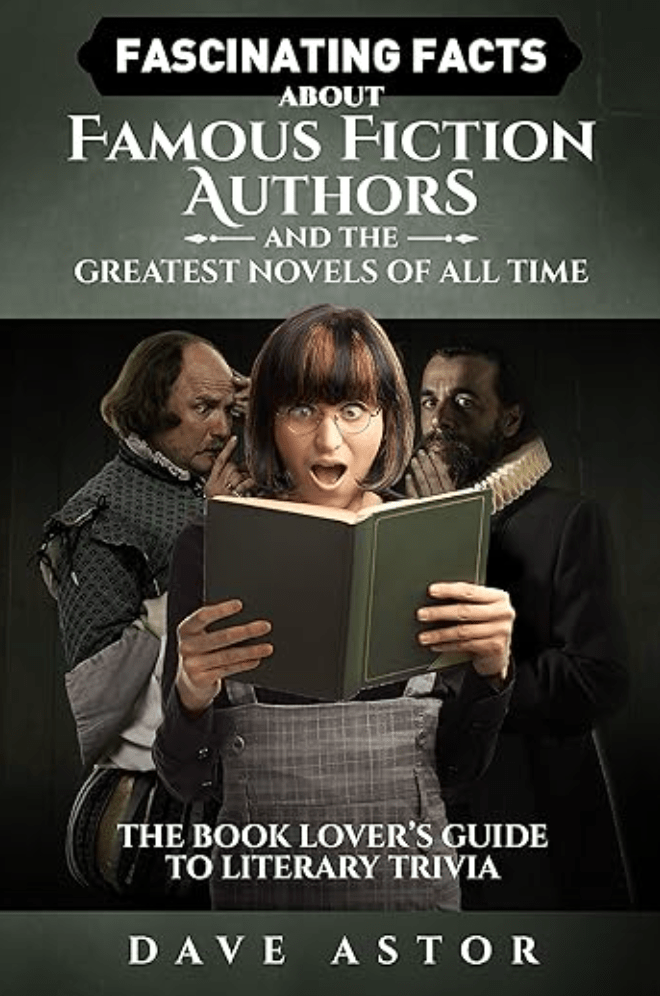

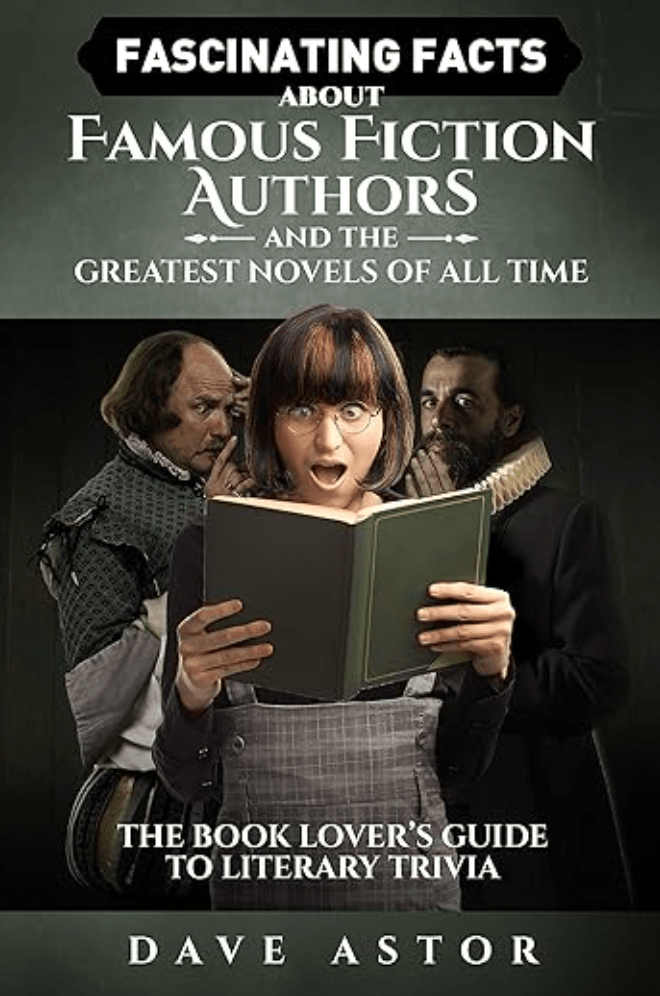

I’m also the author of a 2017 literary-trivia book…

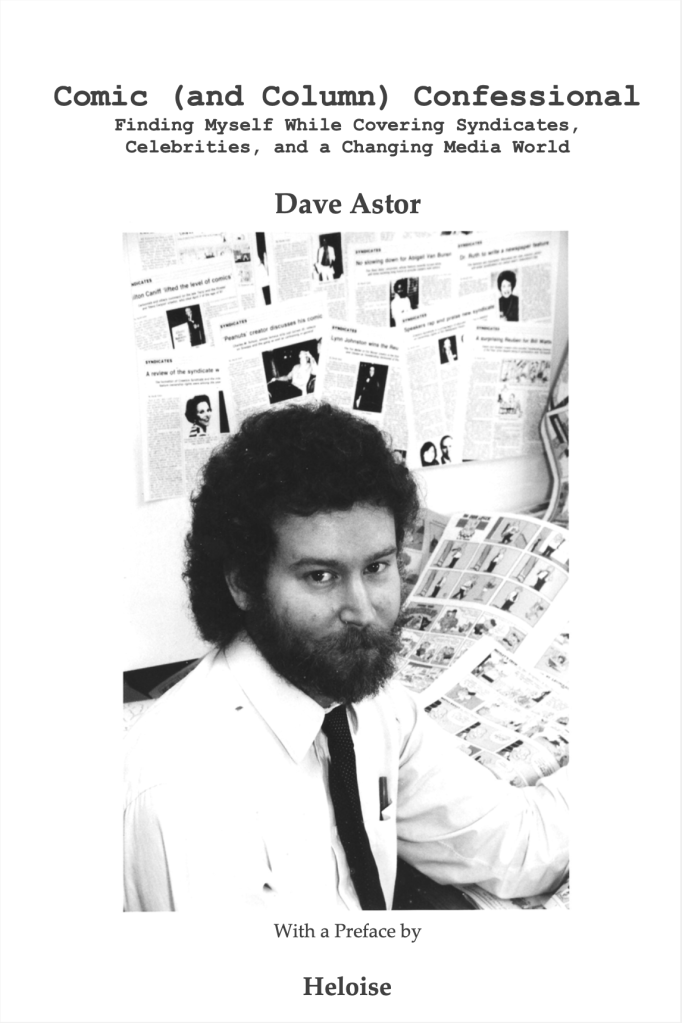

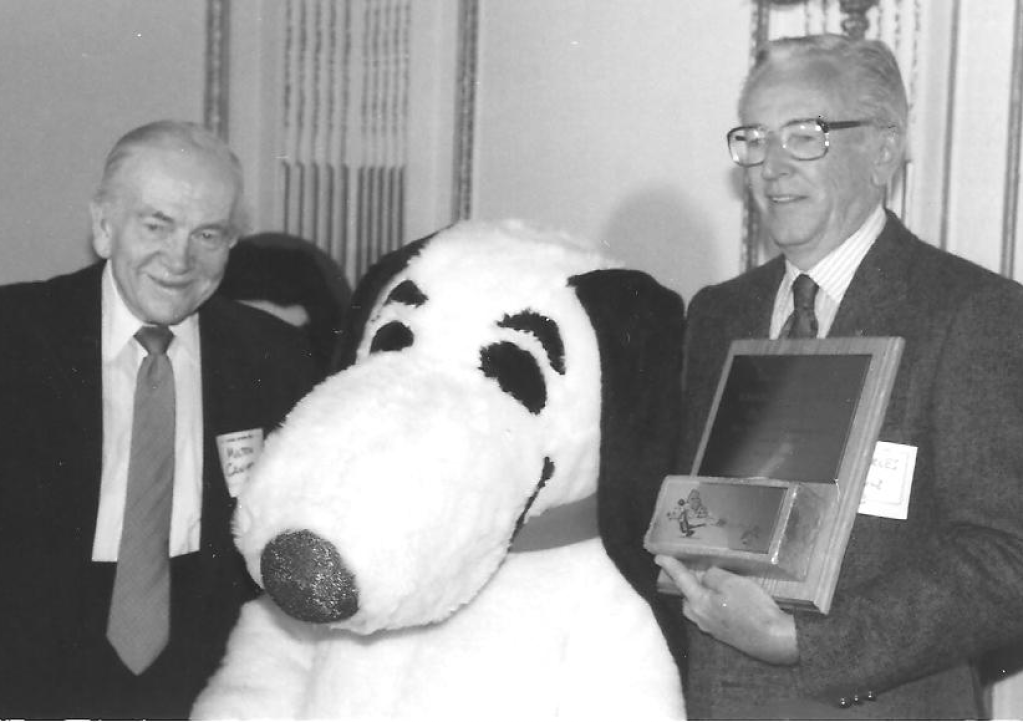

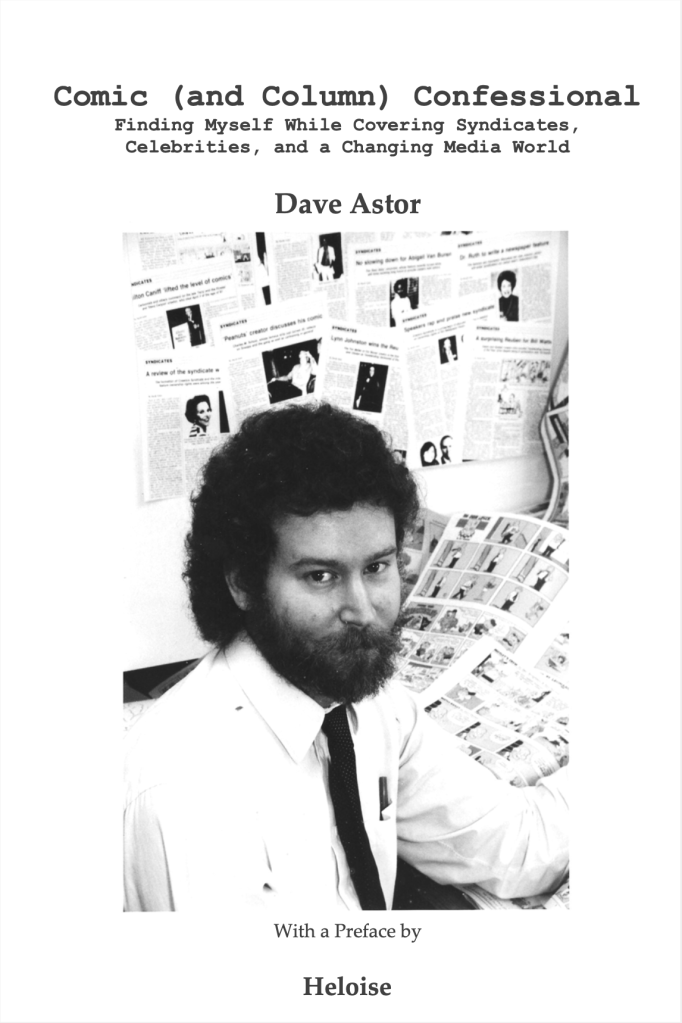

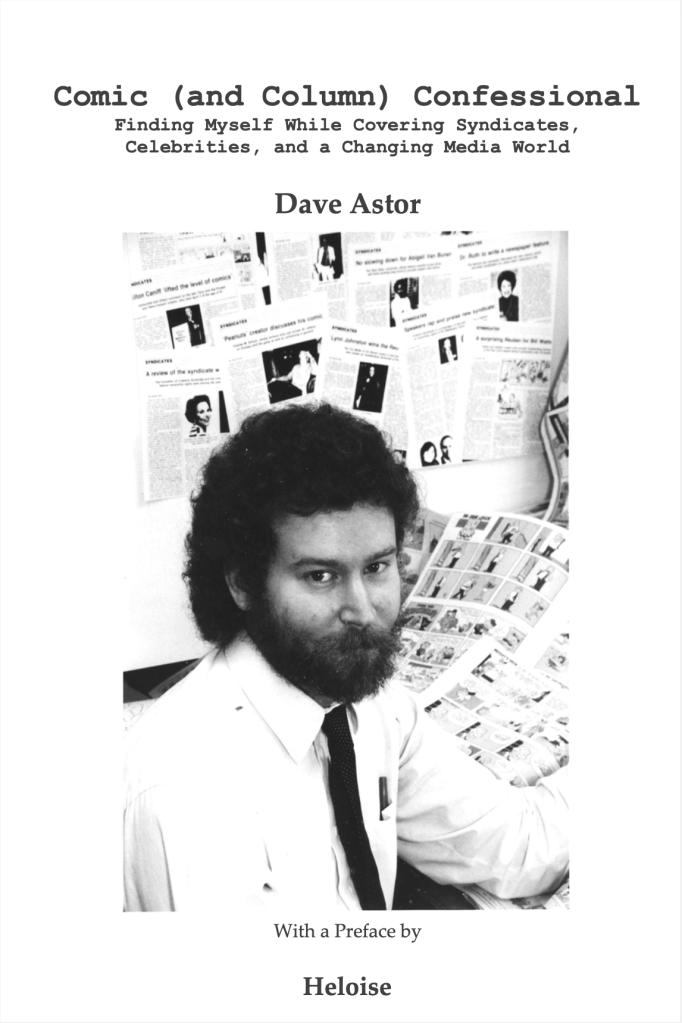

…and a 2012 memoir that focuses on cartooning and more.

In addition to this weekly blog, I write the 2003-started/award-winning “Montclairvoyant” topical-humor column every Thursday for Montclair Local. The latest piece — about another LONG Township Council meeting and more — is here.