Sue Grafton

Last week, I wrote about incompetent characters in literature. So, naturally I’ll write this week about…Valentine’s Day yesterday. Oops, just kidding; I’m going to discuss competent characters in literature.

That can mean smart people, handy people, socially adept people, etc. They might be skilled in many areas, or skilled in some ways and not in others.

Obviously, detectives are among the protagonists who come to mind, although many of them are more competent in their work than in their personal lives. For instance, Sherlock Holmes is a brilliant sleuth with loner and eccentric traits in Arthur Conan Doyle’s novels and stories. Val McDermid’s Karen Pirie is also highly intelligent and driven in her cold-case work while not being as successful in off-duty life. Sue Grafton’s self-deprecating Kinsey Millhone is a brainy, brave, dogged, and witty private investigator who had two failed marriages, eats too much junk food, etc.

I’m currently working my way through — and loving — the Millhone-starring “alphabet mysteries” (now reading M is for Malice).

Other memorably competent characters? Hermione Granger is as book-smart as they come, and also has plenty of common sense in J.K. Rowling’s Harry Potter series. Those books’ wizards — including Albus Dumbledore and Minerva McGonagall — are obviously quite capable, too, as is another wizard: Gandalf in J.R.R. Tolkien’s The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings trilogy.

In Stieg Larsson’s trilogy that starts with The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo, abuse survivor Lisbeth Salander is a determined genius with computers.

Preteen-then-teen Francie Nolan is wise beyond her years — both academically and as a navigator of difficult family dynamics — in Betty Smith’s A Tree Grows in Brooklyn.

When one thinks of Charlotte Bronte’s Jane Eyre character, competent is one of the first adjectives that comes to mind. Whatever she does — whether being a governess, a teacher, or generally maneuvering through the difficulties of her oft-challenging life — she does well.

Also quite skilled — and with a strong sense of morality — is attorney Atticus Finch of Harper Lee’s To Kill a Mockingbird.

Another classic, Willa Cather’s My Antonia, features a title character (Antonia Shimerda) who’s a very competent farm spouse and parent.

In the sci-fi area, we have protagonists like Mark Watney, who has to be unusually clever and innovative to survive when stranded on Mars in Andy Weir’s The Martian. Twentieth-century Black woman Dana Franklin also has to be really skilled to deal with and survive involuntary time travel to and from the slave-holding American South in Octavia E. Butler’s Kindred.

Your thoughts about, and examples of, competent characters in fiction?

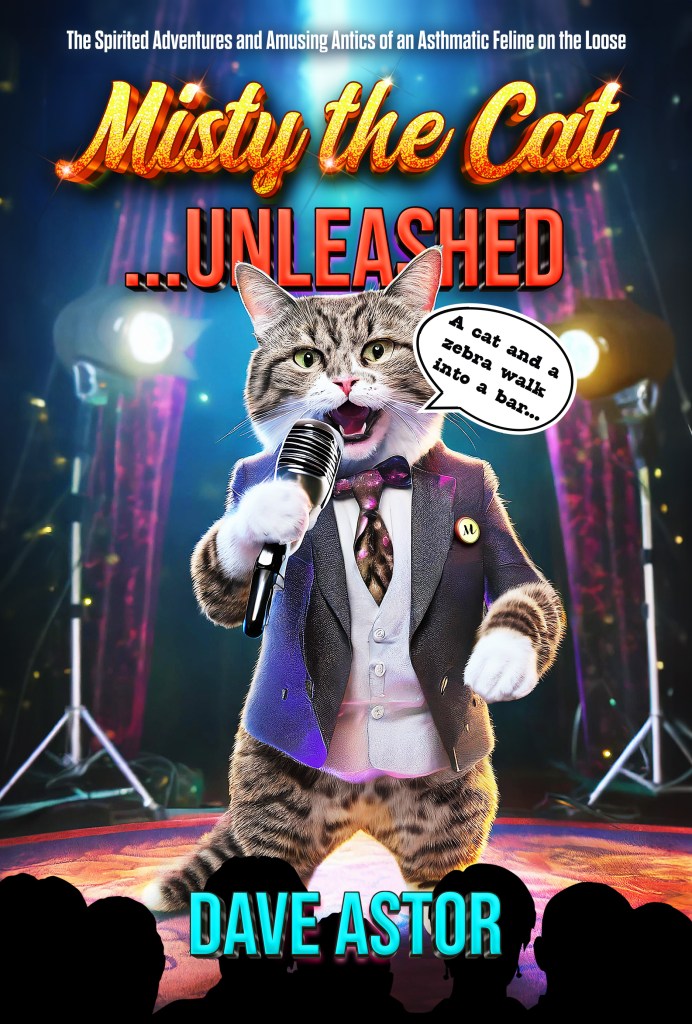

Misty the cat says: “This must be one of Norman Rockwell’s larger paintings.”

My comedic 2024 book — the part-factual/part-fictional/not-a-children’s-work Misty the Cat…Unleashed — is described and can be purchased on Amazon in paperback or on Kindle. It’s feline-narrated! (And Amazon reviews are welcome. 🙂 )

This 90-second promo video for the book features a talking cat: 🙂

I’m also the author of a 2017 literary-trivia book…

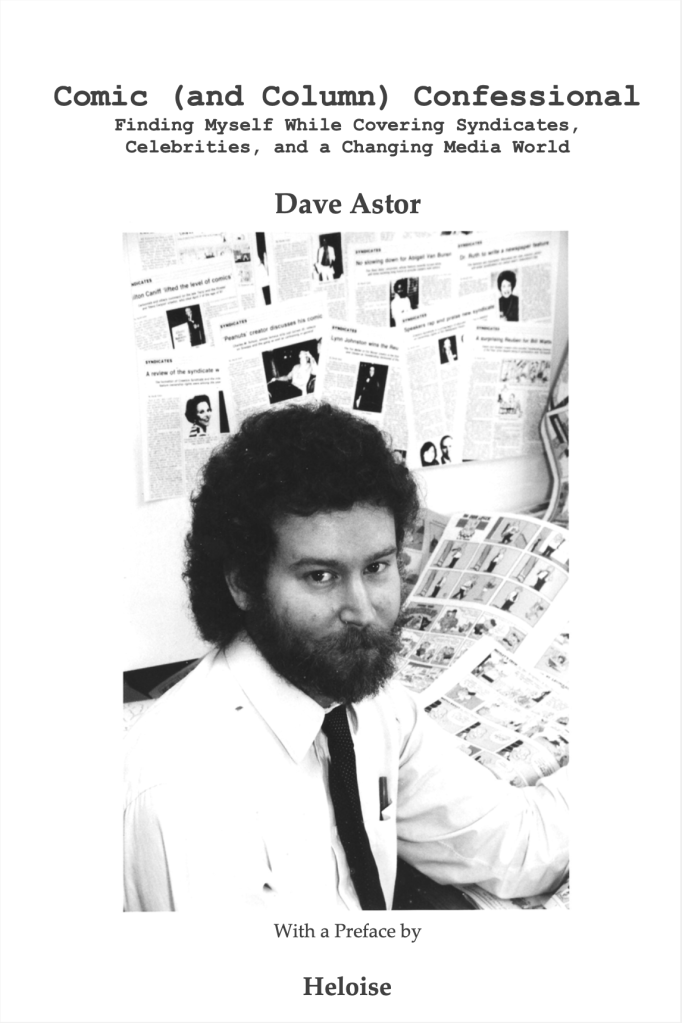

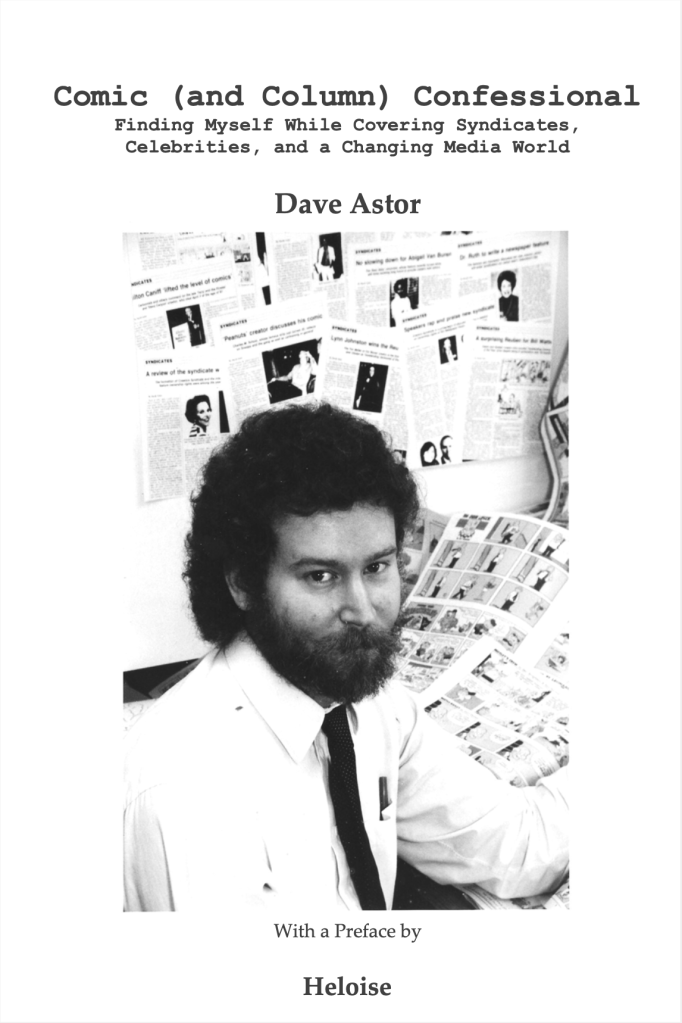

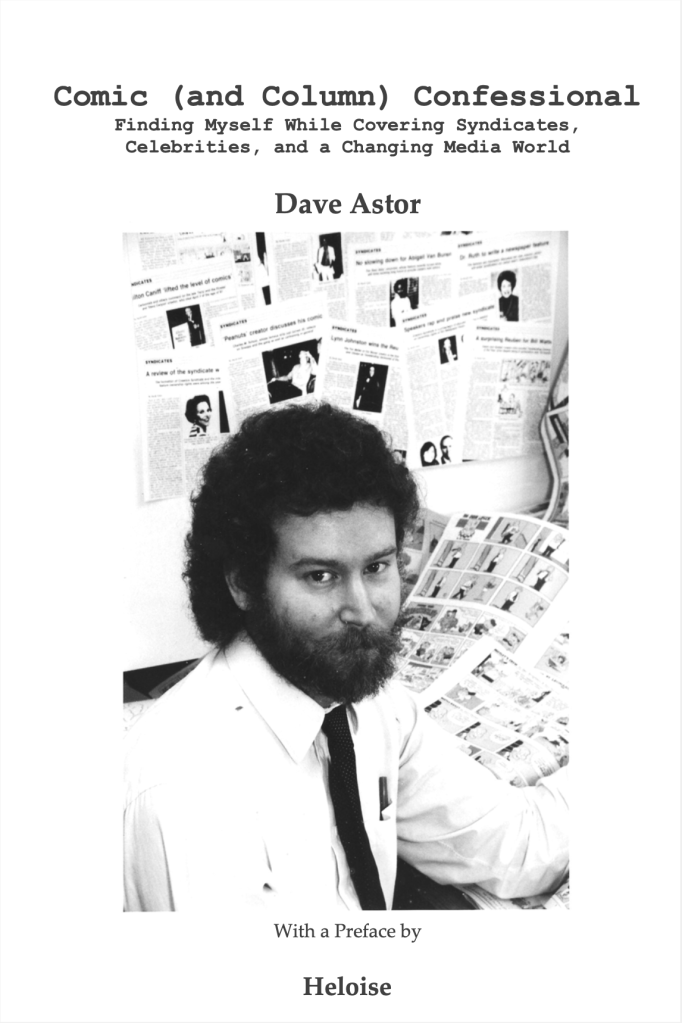

…and a 2012 memoir that focuses on cartooning and more, including many encounters with celebrities.

In addition to this weekly blog, I write the 2003-started/award-winning “Montclairvoyant” topical-humor column every Thursday for Montclair Local. The latest piece — about a congressional candidate’s welcome win and various weird maps — is here.